Reading Code Like a Compiler

Imagine trying to read an entire book while

focusing on only one or two words at a time

We use compilers every day to parse our code, find our programming mistakes and then help us fix them. But how do compilers read and understand our code? What does our code look like to them?

We tend to read code like we would read a human language like English. We don’t see letters; we see words and phrases. And in a very natural way we use what we just read, the proceeding sentence or paragraph, to give us the context we need to understand the following text. And sometimes we just skim over text quickly to gleam a bit of the meaning without even reading every word.

Compilers aren’t as smart as we are. They can’t read and understand entire phrases or sentences all at once. They read text one letter, one word at at time, meticulously building up a record of what they have read so far.

I was curious to learn more about how compilers parse text, but where should I look? Which compiler should I study? Once again, like in my last few posts, Crystal was the answer.

Crystal: A Compiler Accessible to Everyone

Crystal is a unique combination of simple, human syntax inspired by Ruby, with the speed and robustness enabled by static types and the use of LLVM. But for me the most exciting thing about Crystal is how the Crystal team implemented both its standard library and compiler using the target language: Crystal. This makes Crystal’s internal implementation accessible to anyone familiar with Ruby. For once, you don’t have to be a hard core C or C++ developer to learn how a compiler works. Reading code not much more complex than a Ruby on Rails web site, I can take a peek under the hood of a real world compiler to see how it works internally.

Not only did the Crystal team implement their compiler using Crystal, they also wrote it by hand. Parsing is such a tedious task that often developers use a parser generator, such as GNU Bison, to automatically generate the parse code given a set of rules. This is how Ruby works, for example. But the Crystal team wrote their parser directly in Crystal, which you can read in parser.cr.

Along with a readable compiler, I need a readable program to compile. I decided to reuse the same array snippet from my last post:

arr = [12345, 67890] puts arr[1]

This tiny Crystal program creates an array of two numbers and then prints out the second number. Simple enough: You and I can read and parse these two lines of code in one glance and in a fraction of a second understand what it does. Even if you’re not a Crystal or Ruby developer this syntax is so simple you can still understand it.

But the Crystal compiler can’t understand this code as easily as we can. Parsing even this simple program is a complex task for a compiler.

How the Crystal Compiler Sees My Code

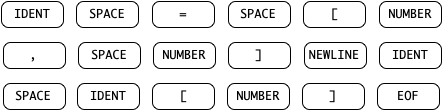

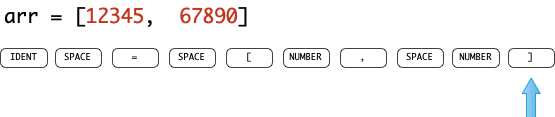

Before parsing or running the code above, Crystal converts it into a series of tokens. To the Crystal compiler, my program looks like this:

The first IDENT token corresponds to the arr variable at the beginning of the

first line. You can also see two NUMBER tokens: the Crystal tokenizer

code

converted each series of numerical digits into single tokens, one for 12345 and

the other for 67890. Along with these tokens you can also see other tokens for

punctuation used in Crystal syntax, like the equals sign and left and right

square brackets. There is also a new line token and one for the end of the

entire file.

Reading a Book One Word at a Time

To understand my code, Crystal processes these tokens one at a time, stepping tediously through the entire program. What a slow, painful process!

How would we read if we could only see one word at a time? I imagine covering the book I’m trying to read with a piece of paper or plastic that had a small hole in it… and that through the hole I could only see one word at a time. How would I read one entire page? Well, I’d have to move the paper around, showing one word and then another and another. And how would I know where to move the paper next? Would I simply move the paper forward one word at at time? What if I forgot some word I had seen earlier? I’d have to backtrack - but how far back to go? What if the meaning of the word I was looking at depended on the words that followed it? This sounds like a nightmare.

To read like this, if it was even possible at all, I’d have to have a well thought out strategy. I’d have to know exactly how to move that plastic screen around. When you can only read one word at a time, deciding which word to read next becomes incredibly important. I would need an algorithm to follow.

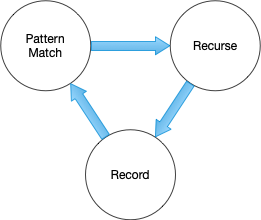

This is what a parser algorithm is: Some set of rules the parse code can use to interpret each word, and, equally important, to decide which word to read next. Crystal’s parse code is over 6000 lines long, so I won’t attempt to completely explain it here. But there’s an underlying, high level algorithm the parse code uses:

First, the parser compares the current token, and possibly the following or previous tokens as well, to a series of expected patterns. These patterns define the syntax the parser is reading. Second, the parser recurses. It calls itself to parse the next token, or possibly multiple next tokens depending on which pattern the parser just matched. Finally, the parser records what it saw: which pattern matched the current token and the results of the recursive calls to itself, for future reference.

Matching a Pattern

The best way to understand how this works is to see it in action. Let’s follow along with the Crystal compiler as it parses the code I showed above:

arr = [12345, 67890] puts arr[1]

Recall Crystal already converted this code into a token stream:

(To be more accurate, Crystal actually converts my code into tokens as it goes. The parse code calls the tokenizer code each time it needs a new token. But this timing isn’t really important.)

As you might expect, Crystal starts with the first token, IDENT.

What does this mean? How does Crystal interpret arr? IDENT is short for

identifier, but what role does this identifier play? What meaning does arr have

in my code?

To decide on the correct meaning, the Crystal parser compares the IDENT token

with a series of patterns. For example Crystal looks for patterns like:

-

a ternary expression

a ? b : c -

a range

a..b -

an expression using a binary operator, such as:

a + b, etc. -

and many more…

It turns out none of these patterns apply in this case, and Crystal ends up

selecting a default pattern which handles the most common code pattern: a

function call. Crystal decides that when I wrote arr I intended to call a

function called arr.

I often tell people I work with at my day job that I have really bad memory.

And it’s true. I constantly have to google the syntax or return values of

functions. I often forget what some code means even just a month after I wrote

it. And the Crystal compiler is no better: As soon as it processes that IDENT

token above, it has to write down what it decided that token meant or else it

would forget.

To record the function call, Crystal creates an object:

As we’ll see in a moment, Crystal builds up a tree of these objects, called an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). The AST will later serve as a record of the syntactic structure of my code.

Recursively Calling Itself

Parsing is inherently a recursive process. Unlike English text, Crystal expressions can be nested one inside another to any depth. Although I suppose English grammar is somewhat recursive and can be nested to some degree. I wonder if the grammars for some other human languages are more recursive than English? Interesting question.

For parsing a programming language like Crystal, the simplest thing for the parser code to do is recursively call itself. And it does this based on the pattern it just matched. For example, if Crystal had parsed a plus sign, it would need to recursively call itself to parse the values that appeared before and after the plus.

In this example, Crystal has to decide what arguments to pass to this call to

the arr function. Did I write arr(1, 2, 3) or just arr? Or arr()? What were

the values 1, 2 and 3? Each of these could be a complex expression in their own

right, maybe appearing inside of parentheses, a compound value like an array or

maybe yet another function call.

To find the arguments of the function call, inside the recursive call to the parse code Crystal proceeds forward to process the next two tokens:

Crystal skips over the space, and then encounters the equals sign. Suddenly

Crystal realizes it was wrong! The arr identifier wasn’t a reference to a

function at all, it was a variable declaration. Yes, sometimes compilers change

their minds while reading, just like we do!

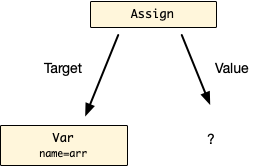

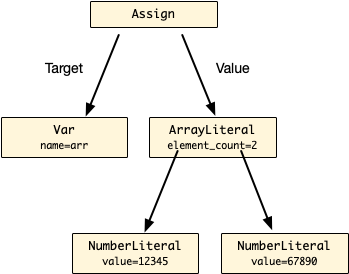

Recording an AST Node

To record this new, revised syntax, Crystal changes the Call AST node it

created earlier to an Assign AST node, and creates a new Var AST node to

record the variable being assigned to:

Now the AST is starting to resemble a tree. Because of the recursive nature of parse algorithm, this tree structure is an ideal way of record what the compiler has parsed so far. Trees are recursive too: Each branch is a tree in its own right.

Rinse and Repeat

But what value should Crystal assign to that variable? What should appear in

the AST as the value attribute of the Assign node?

To find out, the Crystal compiler recursively calls the same parsing algorithm

again, but starting with the [ token:

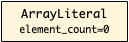

Following the pattern match, record and recurse process, the Crystal compiler

once again matches the new token, [, with a series of expected patterns. This

time, Crystal decides that the left bracket is the start of literal array

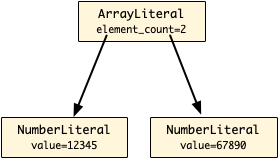

expression and records a new AST node:

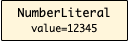

But before inserting it into the syntax tree, Crystal recursively calls itself to parse each of the values that appear in the array. The array literal pattern expects a series of values to appear separated by spaces, so Crystal proceeds to process the following tokens, looking for values separated by commas:

After encountering the comma, Crystal recursively calls the same parse code again on the previous token or tokens that appeared before the comma, because the array value before the comma could be another expression of arbitrary depth and complexity. In this example, Crystal finds a simple numeric array element, and creates a new AST node to represent the numeric value:

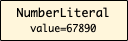

After reading the comma, Crystal calls its parser recursively again, and finds the second number:

Remember Crystal has a bad memory. With all these new AST nodes, Crystal will quickly forget what they mean. Fortunately, Crystal reads in the right square bracket and realizes I ended the array literal in my code:

Now those recursive calls to the parse code return, and Crystal assembles these new AST nodes:

…and then places them inside the larger, surrounding AST:

After this, these recursive calls return and the Crystal compiler moves on to parse the second line of my program.

A Complete Abstract Syntax Tree

After following the Crystal parser for a while, I added some debug logging code to the compiler so I could see the result. Here’s my example code again:

arr = [12345, 67890] puts arr[1]

And here’s the complete AST the Crystal compiler generated after parsing my code. My debug logging indented each line to indicate the AST structure:

<Crystal::Expressions exp_count=3 >

<Crystal::Require string=prelude >

<Crystal::Assign target=Crystal::Var value=Crystal::ArrayLiteral >

<Crystal::Var name=arr >

<Crystal::ArrayLiteral element_count=2 of=Nil name=Nil >

<Crystal::NumberLiteral number=12345 kind=i32 >

<Crystal::NumberLiteral number=67890 kind=i32 >

<Crystal::Call obj= name=puts arg_count=1 >

<Crystal::Call obj=arr name=[] arg_count=1 >

<Crystal::Var name=arr >

<Crystal::NumberLiteral number=1 kind=i32 >

Each of these values is a subclass of the Crystal::ASTNode superclass.

Crystal defines all of these in the

ast.cr

file. Some interesting details to note:

-

The top level node is called

Expressions, and more or less holds one expression per line of code. -

The second node, the first child node of

Expressions, is calledRequire. The surprise here is that I didn’t even put arequirekeyword in my program! Crystal silently insertsrequire preludeto the beginning of all Crystal programs. The “prelude” is the Crystal standard library, the code that definesArray,Stringmany other core classes. Reading the AST allows us to see how the Crystal compiler does this automatically. -

The third node and its children are the nodes we saw Crystal create above for my first line of code, the array literal and the variable it is assigned to.

-

Finally, the last branch of the tree shows the call to

puts. This time Crystal’s default guess about identifiers being function calls was correct. Another interesting detail here is that the inner call to the[]function was not generated by an identifier, but by the[token. This was one of the patterns the Crystal parser checked for after one of the recursive parse calls.

Next Time

What’s the point of all of this? What does the Crystal compiler do next with the AST? This tree structure is a fantastic summary of how Crystal parsed my code, and, as we’ll see later, also provides a convenient way for Crystal later to process my code and transform it in different ways.

When I have time, I plan to write a few more posts about more of the inner workings of the Crystal compiler and the LLVM framework, which Crystal later uses to generate my x86 executable program.