Exploring Ruby’s Regular Expression Algorithm

|

| According to Wikipedia, Oniguruma means “Devil’s Chariot” in Japanese |

We’re all familiar with regular expressions; they are “the developer’s swiss army knife.” Whatever sort of information you need to find, whatever sort of text you need to parse, there’s always a way to do it using a regular expression search. In fact, you’ve probably been using regular expressions for much longer than you have been using Ruby - regular expressions have been included in almost every major programming language for many years: Perl, Javascript, PHP, Java, etc. Ruby was invented in mid-1990’s, while regular expressions were invented in the 1960s, thirty years earlier!

But how do regular expressions actually work? If you’re interested in learning more about the computer science theory behind regular expression engines, you should read a fantastic series of three articles written by Russ Cox:

- Regular Expression Matching Can Be Simple And Fast (2007)

- Regular Expression Matching: the Virtual Machine Approach (2009), and:

- Regular Expression Matching in the Wild (2010).

I won’t repeat everything that Russ wrote again here today. But I will quickly note that Ruby uses the “Non-recursive Backtracking Implementation” discussed in the second article, which means that it does exhibit the same exponentially slow performance as Perl does for pathological regex expressions. In other words, this means that Ruby is NOT using the most optimal regex algorithm available, Thompson NFA, that Russ described in the first article.

Today I’m going to take a close look at Oniguruma, the regular expression engine used by Ruby. Using some simple diagrams I’ll illustrate how it works in detail for a few simple regex pattern examples. Read on to get a sense of what happens inside of Ruby every time you use a regular expression - there’s more to it than you might think!

Oniguruma

Since version 1.9 MRI Ruby has implemented regular expressions using a slightly modified version of an open source C library called “Oniguruma,” also used by PHP. Along with providing all of the standard regex features, Oniguruma is nice since it handles multibyte characters very well, such as Japanese text.

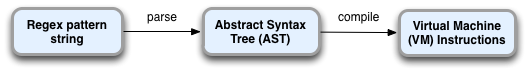

At a very high level, here’s what happens when you first pass a regex pattern to Oniguruma:

In the first step, Oniguruma reads the regex search pattern, tokenizes it and parses it into a tree structure containing a series of syntax nodes - an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). This is very similar to how Ruby itself parses your Ruby program. In fact, you can think of Oniguruma’s regex engine as a second programming language that is embedded right inside of Ruby. Whenever you use a regex pattern in your Ruby code, you’re really writing a second program in an entirely different language. After parsing your search pattern, Oniguruma compiles it into a series of instructions that will later be executed by a virtual machine. These instructions implement a state machine, as Russ Cox described in his articles.

Later when you actually execute a search using a regex pattern, Oniguruma’s virtual machine will execute the search, simply following the instructions that were previously compiled, running them against a given target string.

This week in order to understand how Oniguruma works internally and to see how its algorithm compared to what Russ Cox described, I recompiled Ruby 2.0 (ruby-head) from source after setting a couple of special compiler flags: ONIG_DEBUG_COMPILE and ONIG_DEBUG_MATCH. Setting these flags enabled me to see a lot of debug output from Oniguruma as I ran some regex searches, showing me which Oniguruma VM instructions the regex pattern was compiled to and what happened when Oniguruma’s VM ran the instructions. Here’s what I found....

Example 1: Matching a simple substring

Here’s a very simple Ruby script that searches for the word “brown” in a target string:

str = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog." p str.match(/brown/)

If I run this using my modified version of Ruby, I see lots of additional debug output (much more than I display here):

$ ruby regex.rb PATTERN: /brown/ (US-ASCII) optimize: EXACT_BM exact: [brown]: length: 5 code length: 7 0:[exact5:brown] 6:[end] match_at: str: 140261368903056 (0x7f912511b590) etc ... size: 44, start offset: 10 10> "brown f..." [exact5:brown] 15> " fox ju..." [end] #<MatchData "brown">

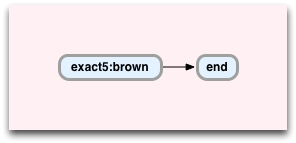

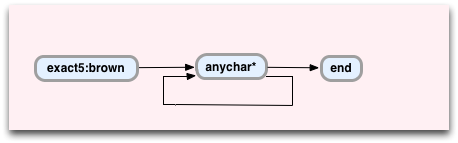

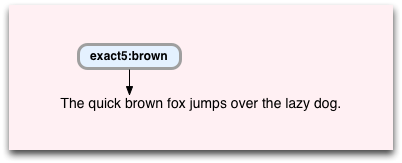

The key here is the text “0:[exact5:brown] 6:[end]” - this line describes the two VM instructions that Oniguruma has compiled the /brown/ pattern into. Here’s what this regex program looks like:

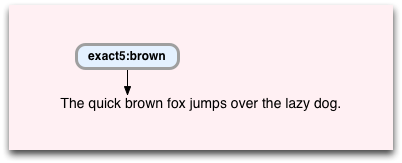

You can think of this diagram as the state machine for the /brown/ search:

- exact5:brown checks the target string at the current position to see whether the 5 letters “brown” appear there, and

- end means the search is over; it returns the characters matched so far and stops.

When running a regex search Oniguruma steps through the VM instructions and the target string at the same time. Let’s walk through how this works for my example; first, the exact5:brown instruction is executed on the target string at the location where the word “brown” appears:

How did Oniguruma know where to start? Well, it turns out that it contains an optimizer that decides where to start the regex search based on the target string and the first VM instruction. You can see evidence of that above: “optimize: EXACT_BM... exact: [brown]: length: 5... start offset: 10”. In this case, since Oniguruma knew it was going to look for the word “brown” it jumped ahead to the first appearance of “brown.” Yes, I know this sounds like cheating, but actually this is just a simple optimization to speed up searches for common regex patterns.

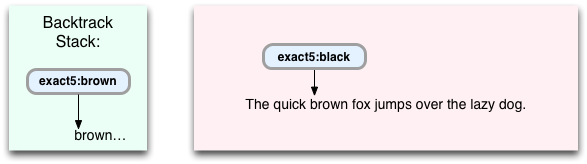

Next, Oniguruma executes the exact5:brown instruction by checking whether the next 5 characters match or not. Since they match, Oniguruma steps past the 5 characters in the target string, and also moves to the next VM instruction:

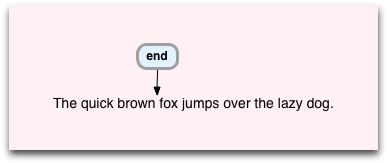

Now, Oniguruma executes the end instruction - which simply means that it is done. Whenever the VM reaches the end instruction it stops, declares success and returns the matching string.

Example 2: matching one string or another

Now let’s take a more complex example and see what happens - in this pattern I want to match either “black” or “brown”:

str = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog." p str.match(/black|brown/)

Running again:

$ ruby regex.rb PATTERN: /black|brown/ (US-ASCII) optimize: EXACT exact: [b]: length: 1 code length: 23 0:[push:(11)] 5:[exact5:black] 11:[jump:(6)] 16:[exact5:brown] 22:[end] match_at: str: 140614855412048 (0x7fe37281c950), ... size: 44, start offset: 10 10> "brown f..." [push:(11)] 10> "brown f..." [exact5:black] 10> "brown f..." [exact5:brown] 15> " fox ju..." [end] #<MatchData "brown">

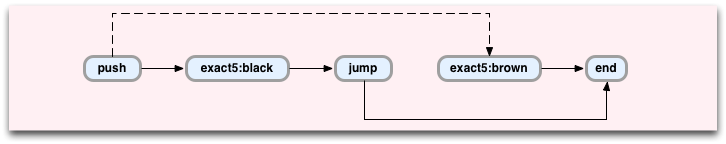

Again, the key line is: “0:[push:(11)] 5:[exact5:black] 11:[jump:(6)] 16:[exact5:brown] 22:[end]”. This is the VM program that will execute our /black|brown/ regex search:

This is a lot more complicated! First of all, above you can see the optimizer is now only looking for the letter “b”: “optimize: EXACT exact: [b]: length: 1”. This is because the words “black” and “brown” both begin with the same letter “b”.

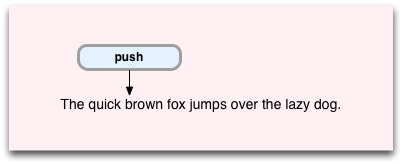

Now let’s step through this more complex regex program, slowly:

The push command executes first, at the first occurrence of “b.” Push pushes the location of another VM instruction and corresponding target string location onto something called the “Backtrack Stack:”

The Backtrack Stack is central to the way Oniguruma works, as we’ll see in a moment. Oniguruma uses it to keep track of alternative match paths through the target string if one path doesn’t lead to a match. Let’s continue this example and you’ll see what I mean.

Above we are now going to execute the exact5:black command on the target string, but where the word “brown” appears. This means that the command will not match, and so the regex search will fail. However, before returning a failure to Ruby, Oniguruma will check the Backtrack Stack to see if some alternative path was saved there. In this case there is one: the exact5.brown command - the second half of my OR condition in /black|brown/. Now Oniguruma pops the exact5:brown command and corresponding target string location off the stack and continues from there:

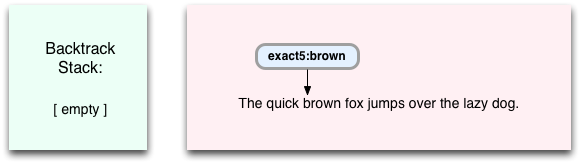

Now there is a match, so Oniguruma steps past the 5 characters and moves to the next instruction:

Now Oniguruma has reached the end instruction again, and so returns the matched characters back to Ruby.

Example 3: the anychar* instruction

Now for my last example today, let’s see what happens when I run this command regex pattern instead:

str = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog." p str.match(/brown.*/)

Now, of course, we want to match “brown” followed by any series of characters until the end of the line. Here’s the debug output:

$ ruby regex.rb PATTERN: /brown.*/ (US-ASCII) optimize: EXACT_BM exact: [brown]: length: 5 code length: 8 0:[exact5:brown] 6:[anychar*] 7:[end] match_at: str: 140284579067040 (0x7f968c80b4a0), ... size: 44, start offset: 10 10> "brown f..." [exact5:brown] 15> " fox ju..." [anychar*] 44> "" [end] #<MatchData "brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.">

And here’s the new state machine:

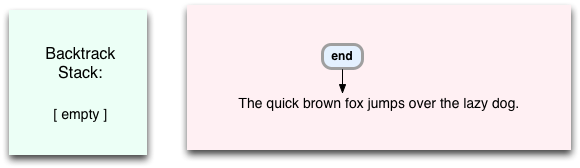

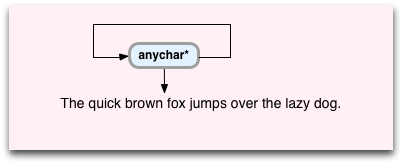

This time you can see a new Oniguruma VM instruction: anychar*. As you can guess, this represents the .* syntax in the regex pattern. Let’s step through the process again and see what happens:

Again, we’ve started at position 10, where “brown” appears. And again it will match, causing Oniguruma to step past “brown” and move to the next instruction:

The anychar* instruction is next. Here’s how anychar* works:

- First, it matches any character, so it always steps forward by one.

- But instead of stepping to the next instruction, Oniguruma loops back and runs anychar* again on the next character.

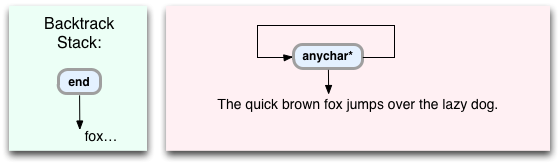

- It also pushes an entry onto the Backtrack Stack for the current character and the next instruction, end in this program:

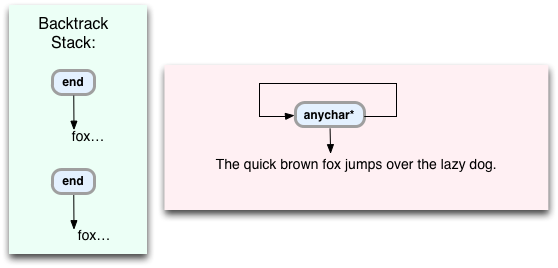

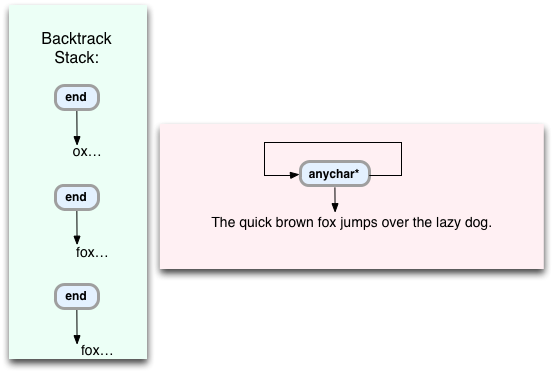

Now from here Oniguruma simply iterates through the rest of the string, repeating the steps above for each character: “brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.” As it iterates through the rest of the target string, it repeatedly saves the end command over and over again onto the backtrack stack:

And again:

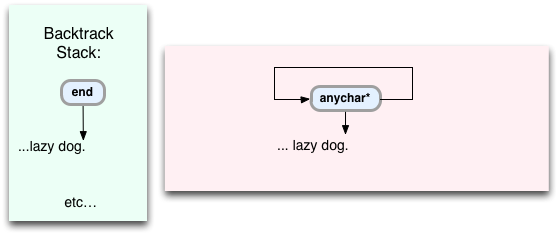

Finally, after a number of iterations Oniguruma reaches the end of the string:

Here anychar* will fail, since there are no more characters left in the string. What happens when there’s a failure and some VM command doesn’t match? Well, like in the previous example Oniguruma will pop the last command off the stack, and continue the search from that point. So in this case it will pop off the end command and the last target string location, pointing at the trailing period. This means Oniguruma will return all of the text up to the end of the string back to Ruby: “brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.”

But why does anychar* need to push every single string location onto the stack as it iterates? The reason is that if there were more commands in the regex pattern after the .*, or if the .* were embedded inside a more complex pattern, then it’s not obvious which string location would eventually lead to a complete match. Oniguruma might need to try them all. In this simple example the pattern matches to the end of the string, so there’s no need to pop off more than one command from the stack.

One interesting detail here is that if you do include other commands after the .* - for example if you search for /.*brown/, then Oniguruma will not use actually use anychar*. Instead it will use another related command called anychar*-peek-next:b for example. This works just like anychar* but instead of pushing every string location onto the Backtrack Stack, it only pushes locations that match the given character, “b” in this case. This optimization works because Oniguruma knows the next character must be a “b.”

A pathological regex pattern

I mentioned at the top that Ruby displays the same poor performance that Perl does when given a pathological, or very complex regex pattern. It’s actually very easy to see this happen using Ruby on your own computer. Try running this very simple regex search on your computer:

str = "aaa" p str.match(/a?a?a?aaa/)

This should run very quickly:

$ time ruby regex.rb #<MatchData "aaa"> ruby regex.rb 0.02s user 0.01s system 30% cpu 0.080 total

However, if you repeat this pattern using 29 repetitions instead of 3 the time required to find the match begins to explode, just as Russ shows in the graph on the left in his first article:

str = "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa" # 29 repetitions p str.match(/a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?a?aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa/)

Running with 29 repetitions:

$ time ruby regex.rb #<MatchData "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa"> ruby regex.rb 17.09s user 0.01s system 99% cpu 17.098 total

Or with 30 repetitions:

$ time ruby regex.rb #<MatchData "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa"> ruby regex.rb 34.00s user 0.01s system 99% cpu 34.025 total

For 31 repetitions the time is 67 seconds and it increases exponentially from there. The reason this happens is that the Backtracking algorithm Oniguruma uses has to iterate through a list of combinations that increases exponentially with the length of the regex pattern. If Oniguruma and Ruby had used the Thompson NFA algorthim that Russ explained this wouldn’t happen!

Scratching the surface

As I said at the beginning, here I’m just scratching the surface of what Oniguruma and Ruby can do. As you probably know, there are many, many more regex operators and options available for you to use, each of which have corresponding Oniguruma VM instructions. In addition, my examples today were extremely simple and straightforward - in a typical Ruby application you might have very complex regex patterns that compile to a program containing hundreds of different Oniguruma VM instructions and many different match paths to follow through the target string.

However, the basic idea will always be the same. Every Oniguruma regex pattern is compiled into a series of VM instructions representing a state machine. When Oniguruma reaches a non-matching state - i.e. a dead end - it will pop off another alternative path through the target string from the Backtrack Stack that might have been left by a push, anychar* or other similar command.