Journey to the center of JRuby

|

Could Jules Verne have imagined something

as complex as the Java Virtual Machine? |

This week I decided to take a look at JRuby, which is a Java implementation of the Ruby interpreter. I’ve heard great things about JRuby, but had never taken the time before to look at how it works internally. What I found was an amazingly complex system involving many different technologies. Following the path of execution through the JRuby stack was like peeling away different layers of an onion - there was always another layer inside.

Read on to join me on a journey through all of these layers; we’ll see how a simple Ruby String method call is handled by Java, how it’s translated into Java byte code, and, ultimately, how that is translated into native machine language by the JVM’s Just In Time (“JIT”) compiler. While you may not be convinced JRuby is the right platform for you - certainly just the hearing word “Java” is enough to send chills down my spine - I hope you’ll come away with a new appreciation of the elegance and sophistication of what the JRuby team has built.

Ruby

One of the nicest things about JRuby is its apparent simplicity: you use it more or less as a drop in replacement for MRI Ruby. That is, once you install JRuby, running a JRuby program works the same way as running a Ruby program. For example, here’s the trivial, one line Ruby program that I’ll look at today:

puts "Journey to the Center of JRuby".upcase

Since I installed JRuby using RVM on my Mac, switching to JRuby and running a Ruby program is as simple as:

$ rvm jruby-head

$ ruby upcase.rb

JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF JRUBY

I could also have used the “jruby” executable in the same way:

$ jruby upcase.rb

JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF JRUBY

But don’t be deceived! Things are not as simple as they seem.

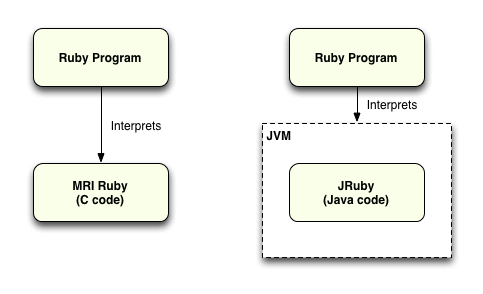

Java

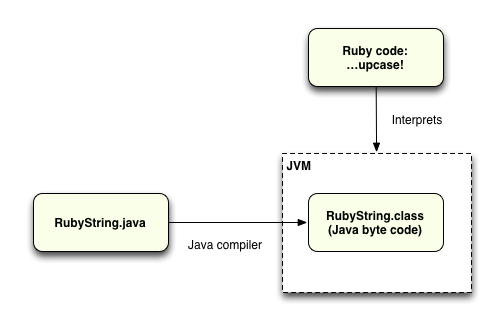

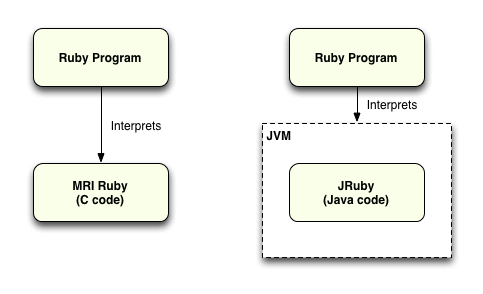

Let’s get started by reviewing the basics of how JRuby works: JRuby is a Java program that interprets Ruby code. Here’s a simple diagram comparing the standard MRI setup with JRuby:

On the left, you can see MRI executing a Ruby program, while on the right JRuby is doing the same thing. The difference is that JRuby is actually a Java program, which means it requires a Java Virtual Machine in order to run. MRI, on the other hand, is written in C and is compiled into native machine language and can run directly as a standalone program on your computer.

Now let’s dive in a take a look at the Java code that implements the Ruby upcase method. Since I installed JRuby using RVM, the JRuby source code is located at this location on my machine:

$ cd ~/.rvm/src/jruby-head/src

And since JRuby uses the “org.jruby” Java package you can find most of the Java source code for JRuby under the “org/jruby” subfolder. Think of Java packages the same way you do Ruby namespaces.

$ cd org/jruby

Now let’s take a look at the JRuby implementation of the Ruby String class, located in the “RubyString.java” file in this folder:

package org.jruby;

... etc ...

/**

* Implementation of Ruby String class

*

* Concurrency: no synchronization is required among readers, but

* all users must synchronize externally with writers.

*

*/

@JRubyClass(name="String", include={"Enumerable", "Comparable"})

public class RubyString extends RubyObject implements EncodingCapable {

... etc ...

private ByteList value;

... etc...

You can see here the RubyString.java file contains a Java class called RubyString which corresponds to the Ruby String class. In fact it looks like the JRuby team used the “@JRubyClass” annotation to indicate this. The one important detail I’ve shown here is that the RubyString class stores the actual string value in an instance variable called value, which is a ByteList Java object.

Farther down in the file we can see the definition of the upcase and upcase! methods:

@JRubyMethod(name = "upcase", compat = RUBY1_8)

public RubyString upcase(ThreadContext context) {

RubyString str = strDup(context.getRuntime());

str.upcase_bang(context);

return str;

}

@JRubyMethod(name = "upcase!", compat = RUBY1_8)

public IRubyObject upcase_bang(ThreadContext context) {

Ruby runtime = context.getRuntime();

if (value.getRealSize() == 0) {

modifyCheck();

return runtime.getNil();

}

modify();

return singleByteUpcase(runtime, value.getUnsafeBytes(),

value.getBegin(), value.getBegin() + value.getRealSize());

}

This Java code is executed when you use the String.upcase method in your Ruby script. This is the version used for Ruby 1.8; the Ruby 1.9 version is slightly more complicated since it handles multibyte characters. JRuby supports a Ruby 1.8 mode and a Ruby 1.9 mode, allowing you to pick the version of Ruby you need for your code. Reading this code and ignoring some of the details, we can see that upcase simply calls strDup and then upcase! on the new copy. Upcase! then returns nil if the size of the string is zero, and calls singleByteUpcase otherwise. On the last line you can see it passes an actual byte array (“byte[]”) into singleByteUpcase.

Just below in RubyString.java, you’ll find the Java singleByteUpcase method that actually performs the upcase operation:

private IRubyObject singleByteUpcase(Ruby runtime, byte[]bytes, int s, int end) {

boolean modify = false;

while (s < end) {

int c = bytes[s] & 0xff;

if (ASCII.isLower(c)) {

bytes[s] = AsciiTables.ToUpperCaseTable[c];

modify = true;

}

s++;

}

return modify ? this : runtime.getNil();

}

Again glossing over some of the details, you can see that JRuby is iterating over the bytes in the string and checking whether each one is lower case or not. If a byte is lower case, it converts it to upper case and sets the modify flag to true. Finally, it returns the same string (this) or else nil if the string was not modified.

That’s enough Java for one day! Let’s move on to see how this Java code is actually executed by your computer.

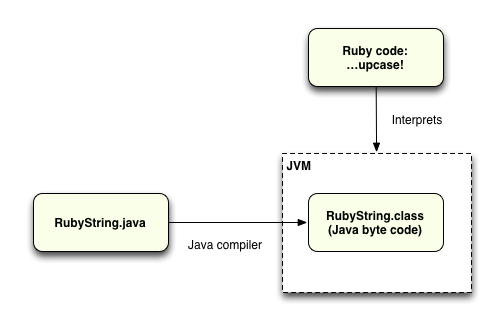

Java byte code

In the diagram above, I showed how the JRuby interpreter is actually a Java program executed by the Java Virtual Machine (“JVM”). However, as you may know, Java is not interpreted the same way that Ruby is. Instead Java is a compiled, statically typed language. This means that the JRuby Java code, like the RubyString.java file we saw above, is compiled into something called “Java byte code” ahead of time. The byte code is what the JVM interprets and executes. Here’s a diagram showing how this process works:

To get a sense of what Java byte code looks like, let’s actually open up the RubyString.class file and see what’s contained inside. Since RubyString.class is a binary file, we need to use a Java utility called “javap” to be able to read and inspect its contents:

$ cd .rvm/src/jruby-head/build/classes/jruby/org/jruby

$ javap -c -private RubyString.class > RubyString.txt

Here the “-c” option means I want to see the actual byte code, and the “-private” option means include the private methods as well, such as singleByteUpcase. Since the output is very large, I’ve redirected it into a file called RubyString.txt. Now let’s take a look inside RubyString.txt at how the singleByteUpcase method looks compiled into byte code:

Compiled from "RubyString.java"

public class org.jruby.RubyString extends org.jruby.RubyObject

implements org.jruby.runtime.encoding.EncodingCapable {

... etc ...

private org.jruby.util.ByteList value;

... etc ...

private org.jruby.runtime.builtin.IRubyObject singleByteUpcase(org.jruby.Ruby, byte[], int, int);

Code:

0: iconst_0

1: istore 5

3: iload_3

4: iload 4

6: if_icmpge 47

9: aload_2

10: iload_3

11: baload

12: sipush 255

15: iand

16: istore 6

18: getstatic #287 // Field ASCII:Lorg/jcodings/specific/ASCIIEncoding;

21: iload 6

23: invokevirtual #288 // Method org/jcodings/specific/ASCIIEncoding.isLower:(I)Z

26: ifeq 41

29: aload_2

30: iload_3

31: getstatic #269 // Field org/jcodings/ascii/AsciiTables.ToUpperCaseTable:[B

34: iload 6

36: baload

37: bastore

38: iconst_1

39: istore 5

41: iinc 3, 1

44: goto 3

47: iload 5

49: ifeq 56

52: aload_0

53: goto 60

56: aload_1

57: invokevirtual #200 // Method org/jruby/Ruby.getNil:()Lorg/jruby/runtime/builtin/IRubyObject;

60: areturn

Wow - that’s crazy! What in the world does it mean? Java byte code is actually a platform independent version of machine language. These cryptic commands, e.g. “istore” and ”baload,” correspond to native, machine language commands that your computer can execute directly. However, the basic idea behind Java is that the same Java byte code will run on any hardware architecture: your i386 Linux or Mac laptop, your Android phone, etc. etc. The JVM, built for whatever platform you are using, interprets these byte codes and executes your program.

I don’t pretend to understand any of the byte code commands above - although it is tempting to look up their meanings somewhere and try to trace this code back to the Java version of singleByteUpcase above. I don’t have time or space for that today, but it is easy to see how some of the commands work, for example:

23: invokevirtual #288 // Method org/jcodings/specific/ASCIIEncoding.isLower:(I)Z

... must be a virtual method call to the “isLower” method of the ASCIIEncoding class. And:

47: iload 5

49: ifeq 56

52: aload_0

53: goto 60

56: aload_1

57: invokevirtual #200 // Method org/jruby/Ruby.getNil:()Lorg/jruby/runtime/builtin/IRubyObject;

60: areturn

... seems to correspond to the last line of Java code in singleByteUpcase:

return modify ? this : runtime.getNil();

However, I’m not sure. I feel like a 19th Century egyptologist trying to understand a newly discovered hieroglyphic passage for the first time.

Assembly Language

Now we’re reaching the deepest, darkest depths of the JRuby system. It turns out that the modern JVMs are sophisticated enough to perform another compilation step internally and convert portions of your Java byte code - the interpreter running your Ruby program - directly into native machine language. This means that running the JRuby interpreter uses native machine language just like using the standard MRI interpreter does, at least for some portions of the code. This is one of the reasons why running a Ruby program with JRuby can often be faster than running it with MRI Ruby!

This last compilation step, which is performed dynamically while your program is running, is called “Just In Time” (JIT) compilation. As the JVM runs your program, whether it’s Java, JRuby or any other program that uses the JVM platform, it monitors which code functions are executed most often. Identifying these as “hotspots,” the JIT compiler inside the JVM will dynamically compile these sections of Java byte code, like what we saw above, into native machine language.

Let’s see how the JIT compiler works for a Ruby program. But first we need to create a hotspot - a bit of code that is executed many times - in order to trigger the JIT compiler. To do that, I’ll just put the call to upcase into a loop, and remove the puts statement so I don’t get drowned in output:

10000.times do

str = "Journey to the Center of JRuby".upcase

end

Now if you set the -J-XX:+PrintCompilation option while running JRuby, you’ll get lots of output showing which Java methods were compiled by the JIT compiler. I’ll redirect the output into a text file so I can search through it more easily:

$ ruby -J-XX:+PrintCompilation upcase.rb > compilation.log

Reading through the compilation.log file:

51 1 3 java.lang.String::equals (88 bytes)

53 2 3 java.lang.Object:: (1 bytes)

54 3 3 java.lang.Number:: (5 bytes)

54 4 3 java.lang.Integer:: (10 bytes)

54 5 1 java.lang.Object:: (1 bytes)

... etc ...

1026 821 4 java.util.ArrayList::get (11 bytes)

1026 903 1 org.jruby.util.ByteList::invalidate (11 bytes)

1026 407 3 org.jruby.util.ByteList::invalidate (11 bytes) made not entrant

1026 899 3 org.jruby.RubyString::singleByteUpcase (61 bytes)

1026 204 3 java.util.ArrayList::get (11 bytes) made not entrant

1027 756 4 org.jruby.util.ByteList::append (36 bytes)

1028 904 1 org.jruby.RubyString::getCodeRange (8 bytes)

At the top of the file we see that many of the basic, intrinsic Java methods like java.lang.String.equals, are compiled into machine language first. This is because the JRuby interpreter is actually quite complex and uses all of these methods often. Later in the file the org.jruby.RubyString::singleByteUpcase method we saw above is compiled since it is executed so many times in my loop.

To finish things off for today, let’s take a look at part of the assembly language that our call to upcase was converted to... it turns out that there’s another JVM option that will actually display the assembly language generated by the JIT compiler. But to use it I first needed to download and build a debug version of the OpenJDK JVM source code (following these instructions, and specifying “make debug_build” instead of “make”).

Here’s what I get running “ruby --version” and “java -version”

$ ruby --version

jruby 1.7.0.dev (ruby-1.9.3-p28) (2012-02-04 9aac4bd) (OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM 1.7.0-internal-debug)

[darwin-amd64-java]

$ java -version

openjdk version "1.7.0-internal-debug"

OpenJDK Runtime Environment (build 1.7.0-internal-debug-pat_2012_02_04_07_35-b00)

OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM (build 23.0-b12-jvmg, mixed mode)

And here’s the command to view the assembly output from the JIT - I got this from Charles Nutter’s list of his favorite JVM options:

$ ruby -J-XX:+PrintOptoAssembly upcase.rb > assembly.log

Finally, here’s a small portion of the assembly.log file:

{method}

- klass: {other class}

- this oop: 0x0000000132798980

- method holder: 'org/jruby/RubyString'

- constants: 0x0000000132780428 constant pool [3032] for 'org/jruby/RubyString' cache=...

- access: 0xc1000002 private

- name: 'singleByteUpcase'

- signature: '(Lorg/jruby/Ruby;[BII)Lorg/jruby/runtime/builtin/IRubyObject;'

- max stack: 4

- max locals: 7

... etc ...

04c testq RBP, RBP # ptr

04f je B44 P=0.001000 C=-1.000000

04f

055 B2: # B50 B3 <- B1 Freq: 0.999

055 movq R8, RBP # spill

058 movq R10, [RBP + #8 (8-bit)] # class

05c movq R11, precise klass org/jruby/RubyString: 0x00007fd0bc06e698:Constant:exact * # ptr

066 cmpq R10, R11 # ptr

069 jne,u B50 P=0.000001 C=-1.000000

069

06f B3: # B4 <- B2 Freq: 0.998999

06f movq RCX, RBP # spill

072 # checkcastPP of RCX

072

072 B4: # B45 B5 <- B3 B44 Freq: 0.999999

072 movq R9, [rsp + #0] # spill

076 testq R9, R9 # ptr

079 je B45 P=0.001000 C=-1.000000

079

07f B5: # B51 B6 <- B4 Freq: 0.998999

07f movq R10, [R9 + #8 (8-bit)] # class

083 movq R11, precise klass org/jruby/Ruby: 0x00007fd0bc06e898:Constant:exact * # ptr

08d cmpq R10, R11 # ptr

090 jne,u B51 P=0.000001 C=-1.000000

... etc...

And there you have it: the actual i386 assembly language code that’s executing our "Journey to the Center of JRuby".upcase Ruby code! We’ve finally reached the “center of JRuby;” we can’t go any farther from here.