My first impression of Rubinius internals

|

| Reading the Rubinius source code is like walking through a well-kept, manicured garden |

This week I decided to take a look at Rubinius; I had heard for a long time that somehow the Rubinius team had “implemented Ruby with Ruby.” That sounded both intriguing and impossible at the same time; I just had to take a look. But even the name itself intimidated me: hearing “Rubinius” somehow led me to expect to see something esoteric or arcane, possibly because it rhymes with “devious.” But since I had just spent a few weeks studying the MRI Ruby interpreter’s C source code, I felt I was ready for anything.

I ended up being pleasantly surprised! Instead of something arcane or cryptic, what I found was beautiful, well documented and easy to understand code. Reading it was like walking around a nicely manicured garden... everything was very perfectly organized and carefully arranged like a series of elegant flowerbeds. In comparison, reading the MRI C source code at times felt like trekking through the Brazilian rainforest at night!

If you’re interested in getting started learning about Ruby interpreter internals then consider looking at Rubinius first; I believe you’ll find it to be a lot easier to understand than the MRI C source code is. Read on to learn more...

What is Rubinius?

There’s a wealth of information out there about Rubinius that I won’t repeat here. To get started you can take at look at the project’s home page, documentation page, and Github repo. There’s also a nice post by Brian Ford from just a few months back called Contributing to Rubinius you should be sure to read as well.

There are few different ways to install Rubinius:

- by downloading a tar-ball

- by cloning the Github repo, or

- by using RVM to install it.

The Rubinius team, including contributions from 100s of different developers, has done a great job at making Rubinius a simple drop in replacement for MRI ruby. Once you have it installed the “ruby” command will execute the Rubinius interpreter instead of the standard MRI C interpreter, and will work exactly the same way, most of the time. You can configure it to emulate Ruby 1.8 or 1.9, and there’s even a separate project called Ruby Spec that measures how much of the MRI implementation Rubinius supports.

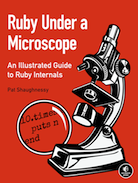

There are a couple of nice diagrams on the Rubinius home page you should look at to get the lay of the land. After using it for only a few days, here’s a diagram of my own mental model that I developed for Rubinius internals:

The way I think of Rubinius is: some of the Ruby standard library methods and classes are implemented with Ruby inside the “kernel” folder, while the rest of the standard library and the core behavior of the language is implemented with C++ code in the “vm/builtin” folder. So when your Ruby program makes a method call to one of the core methods sometimes it will be handled by Ruby code, and other times it will be handled by C++. Along with the C++ standard library method definitions, the Rubinius vm folder also contains code that actually executes your program and includes lots of other magic like a JIT (“just in time”) runtime compiler.

However, just examining the Ruby and C++ implementation of commonly used Ruby classes and methods in the kernel and vm folders was very interesting and worthwhile. Someday I hope to understand more about the rest of the system.

How Rubinius implements String.upcase!

Let’s avoid the C++ code for a few minutes and get started with a simple example of a Ruby core method implemented with Ruby itself: String.upcase! Most of you are probably familiar with upcase! - it converts all of the letters in a given string to upper case, like this:

str = "What started as a toy grew into a labour of love." str.upcase! puts str => "WHAT STARTED AS A TOY GREW INTO A LABOUR OF LOVE."

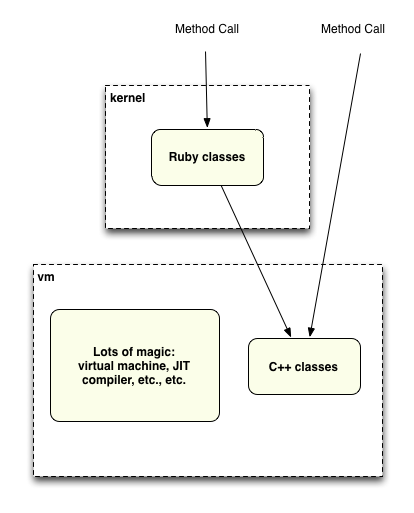

This is from the Rubinius home page, actually: “What started as a toy grew into a labour of love. We love building Rubinius and hope you'll love using it.” It’s not hard at all to find the implementation of String.upcase! - a simple search and you’ll find it in the kernel/common/string.rb file. This diagram shows your Ruby program calling the upcase! method:

Here’s the actual definition:

class String include Comparable attr_accessor :data ... etc ... # Returns a copy of <i>self</i> with all lowercase letters replaced with their # uppercase counterparts. The operation is locale insensitive---only # characters ``a'' to ``z'' are affected. # # "hEllO".upcase #=> "HELLO" def upcase str = dup str.upcase! || str end ## # Upcases the contents of <i>self</i>, returning <code>nil</code> if no # changes were made. def upcase! return if @num_bytes == 0 self.modify! modified = false ctype = Rubinius::CType i = 0 while i < @num_bytes c = @data[i] if ctype.islower(c) @data[i] = ctype.toupper!(c) modified = true end i += 1 end modified ? self : nil end ... etc... end

At the top I’ve shown the declaration of Rubinius’s String class - it’s just a Ruby class like any other. However, in Rubinius there’s an instance variable called data which is set to the actual string data value. You can see this declared near the top using attr_accessor. There’s also a second instance variable called num_bytes which holds the length of the string as an integer value. This instance variable doesn’t have a corresponding attr_accessor call. I’ve also included upcase which calls into the upcase! method after creating a new copy of the string.

The actual upcase! method is fairly easy to understand, since it’s all just plain Ruby:

- If the target string is empty, then return nil

- Otherwise iterate through the characters in the string and replace each lowercase character with the result of the toupper! in the Rubinius::CType module. You can find toupper() in kernel/common/ctype.rb.

- Keep track of whether or not any characters were changed using the modified flag.

- Finally return the target string (self) or else nil if there were no changes made.

The nice thing about seeing upcase! implemented in Ruby is that if I have any questions about how it works or exactly what it does I can just refer to the interpreter’s source code and see exactly what’s going on. With MRI this is impossible unless you’re willing to look at C code. Another nice thing about this code is that it was written to be very readable and easily understood. You might not appreciate this at first glance, but as a comparison here’s the MRI 1.9.3 code that implements upcase! in C:

static VALUE rb_str_upcase_bang(VALUE str) { rb_encoding *enc; char *s, *send; int modify = 0; int n; str_modify_keep_cr(str); enc = STR_ENC_GET(str); rb_str_check_dummy_enc(enc); s = RSTRING_PTR(str); send = RSTRING_END(str); if (single_byte_optimizable(str)) { while (s < send) { unsigned int c = *(unsigned char*)s; if (rb_enc_isascii(c, enc) && 'a' <= c && c <= 'z') { *s = 'A' + (c - 'a'); modify = 1; } s++; } } else { ... even more code deleted from here ... } if (modify) return str; return Qnil; }

Wow! The Rubinius implementation is far simpler and easier to understand at first. Now to be fair, the C MRI code has to deal with low level technical details such as the character encoding and multibyte, unicode character values, while the Rubinius implementation at this level, in the Ruby portion, does not. You might say: “What about the lower level, C++ code in Rubinius - that must be just as ugly and hard to understand as the MRI C is...” Well, let’s take a look!

How Rubinius concatenates two strings

String.upcase! was a very simple example since Rubinius was able to implement the entire method using Ruby. Unfortunately, it’s not always so simple: many of the important core methods and features of the language had to be written using C++ and not Ruby.

But first: Why would Rubinius be a good place to start learning about Ruby internals if I have to learn C++? MRI Ruby was written in C, while much of Rubinius was written in C++. Isn’t C easier to learn and understand than C++? Certainly learning to use the complex, object oriented C++ language effectively and fluently is a lot more difficult to learn than the simple procedural C language. However, for the purposes of learning how a particular Ruby method or class works internally you don’t really need to fully understand all of the power and features of the C++ language. All you really need is to get the gist of what is going on.

Let’s take another example. Here’s the Rubinius definition for the << or concat method:

# Append --- Concatenates the given object to <i>self</i>. If the object is a # <code>Fixnum</code> between 0 and 255, it is converted to a character before # concatenation. # # a = "hello " # a << "world" #=> "hello world" # a.concat(33) #=> "hello world!" def <<(other) modify! unless other.kind_of? String if other.kind_of?(Integer) && other >= 0 && other <= 255 other = other.chr else other = StringValue(other) end end Rubinius::Type.infect(self, other) append(other) end alias_method :concat, :<<

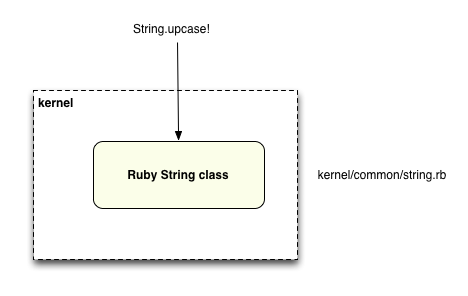

Unlike the String.upcase! function, the Rubinius team had to implement the actual string concatenation part using the append method implemented in C++. So what we have is your Ruby method call handled first by a Ruby method, which in turn calls into the underlying C++ method:

And here’s the C++ code for append:

String* String::append(STATE, const char* other, native_int length) { native_int current_size = byte_size(); native_int data_size = as<ByteArray>(data_)->size(); // Clamp the string size the maximum underlying byte array size if(unlikely(current_size > data_size)) { current_size = data_size; } native_int new_size = current_size + length; native_int capacity = data_size; if(capacity < new_size + 1) { // capacity needs one extra byte of room for the trailing null do { // @todo growth should be more intelligent than doubling capacity *= 2; } while(capacity < new_size + 1); // No need to call unshare and duplicate a ByteArray // just to throw it away. if(shared_ == cTrue) shared(state, cFalse); ByteArray* ba = ByteArray::create(state, capacity); memcpy(ba->raw_bytes(), byte_address(), current_size); data(state, ba); } else { if(shared_ == cTrue) unshare(state); } // Append on top of the null byte at the end of s1, not after it memcpy(byte_address() + current_size, other, length); // The 0-based index of the last character is new_size - 1 byte_address()[new_size] = 0; num_bytes(state, Fixnum::from(new_size)); num_chars(state, nil<Fixnum>()); hash_value(state, nil<Fixnum>()); return this; }

Now there’s a lot going on here that I don’t understand completely; for example:

- What does unlikely mean? ... seems like some sort of C++ compiler optimization trick.

- What does the STATE parameter refer to? I have no idea, to be honest. I’m guessing that it has to do with the way the Rubinius virtual machine works but that’s complete speculation.

- I’m also not sure what hash_value is used for, or exactly how the shared flag is used either. It looks like Rubinius supports shared string values similar to how MRI Ruby does. There’s also a call to unshare in the case where a new buffer is not created.

But aside from some of these details, this code is actually very clean and easy to understand, even if you’re not a C++ wizard. Let’s take it from the top and work down:

- current_size is set to the size of the current string

- Then new_size is set to the new size of the string

- Then, if necessary, we enter a loop that determines how much to increase the size of the current string buffer - it doubles the string size until it’s large enough to fit the current string plus the new string.

- Next if the buffer size needs to be increased, a new ByteArray object is created containing the original string’s data.

- Finally the new string data is appended to the end of the original or new buffer using memcpy, and explicitly null terminated.

Rubinius: a great place to start learning Ruby internals

I hope I’ve whet your appetite a bit today and convinced you to take a look inside of Rubinius to see how it implements Ruby. Beyond being an interesting, alternative implementation of the Ruby interpreter, I think it can also be viewed as a detailed Ruby language reference. Want to know what a certain Ruby String or Array method really does? Just take at look at how it’s implemented! Much of the core language is written directly in Ruby, so it’s an ideal place to start learning if you’re not familiar with C. And the lower level Rubinius C++ method definitions are also fairly easy to follow, much easier than the equivalent MRI C code is in my opinion.