Where does my javascript code go? Backbone, JST and the Rails 3.1 asset pipeline

One of the best things about the Rails framework is that each project looks the same:

Every Rails developer knows to look in “app/models” for the model classes, “app/controllers” for the controller classes, etc. When you start a new project all of this is setup for you, and if you’re a new developer assigned to an existing Rails project you know where to look for things. The way you save and organizing your code files is not simply a convenience... I think it actually effects the way you think about code. Well organized code directories leads to well organized code!

But these days most modern web sites include a large amount of Javascript code, not only server-side web page generation. And recently there have been a lot of exciting new ideas and technologies in the Javascript space, as well as some innovative and dramatic changes to Rails itself with 3.1 coming out soon. All of this lead me to ask myself: where should I put my Javascript code in a Rails 3.1 app? The answer is not at all obvious!

Today I’m going to show off two interesting Rails projects and focus on how their developers have chosen to organize their Javascript code files. Hopefully this will help you decide how to organize your Javascript code files... at least until the Rails community agrees on a single convention.

Ancient history: 2010 and before

Before the asset pipeline was introduced in the Rails 3.1 beta this year - as I write this the latest version of Rails is 3.1.0.rc4 - all of the javascript code in a Rails web site was typically stored under the “public” folder, along with other static content:

Javascript code was considered just another type of static web asset file, like stylesheets and images, and was simply downloaded to the client browser by Apache or Nginx, without the Rails framework getting involved at all.

The biggest problem with this was that each static file, whether an image, CSS stylesheet or Javascript code file, required a separate HTTP request to the server. The Rails 3.1 asset pipeline, which I’ll get to in a moment, solves this problem in Rails 3.1 by combining all of the static files together into a single download request.

However, in my opinion performance is not actually the biggest problem here. In most of my Rails projects the performance impact of having many small files was small. Instead, the biggest problem I faced using Rails 3.0 and earlier versions was how to organize my Javascript code. In a typical Rails 3.0 project, all of the vendor Javascript code (e.g. JQuery) is saved in a series of .js files in the public/javascripts folder, and any custom javascript is all combined together in one large “application.js” file:

Enter Backbone

Backbone.js is a great way to organize your client Javascript code into the same MVC (model, view, controller) pattern that your Rails server application uses. Backbone was written by and is still maintained by DocumentCloud. Just like in Rails, you use models to represent data, views to render the data, and controllers to coordinate between the two. It also has an object called a “collection” which manages a list of models. Backbone was also designed with a Rails backend in mind, and is easy to connect to a server application using JSON to transfer data back and forth.

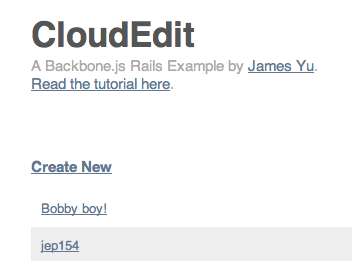

Aside from the basic documentation, there’s a great Backbone/Rails tutorial out there by James Yu; James walks you step by step through creating a simple Ajax/Backbone app that allows you to create and edit documents in a single page:

James posted his Rails 2.3.8 app on github, so you can just download the code and try it out yourself. I won’t repeat everything from James’s tutorial here since he does a fantastic job of describing the code details.

I also created a scaffold for CloudEdit on ScaffoldHub, which will setup the code from CloudEdit inside your own Rails 3 app with a single command:

While working on this scaffold, I spent some time examining how James organized his Javascript code, so I could identify the files to include in the scaffold. I actually found this to be one of the most interesting and useful things from the CloudEdit sample. Here’s how James did it - first his server side Ruby code went into the usual locations:

Aside from those two “JST” files, this is all standard Rails. The interesting part was how James setup his Backbone javascript files:

Note how James used MVC pattern in his code layout for both for the Rails server code: app/controllers, app/models, app/views and for the client side Javascript code: public/javascripts/controllers, public/javascripts/models, public/javascripts/views, plus public/javascript/collections which is new for Backbone.

This is what I like the most about Backbone: it organizes my code! No longer do I have everything combined together in one large application.js file... it’s all split up into different classes that play the same MVC roles that I use in my Rails app. And James has organized the code for these classes in separate folders that are easy to find and remember.

JST: Javascript views evaluated on the client side

JST stands for “Javascript Templates” and is an open source project that’s been around for a number of years now. Backbone makes it easy to use JST to construct the HTML generated for each Javascript view object. Note how James created 3 views in his application, called show.js, index.js, and notice.js, all stored in the app/javascripts/views folder. These contain the Backbone code required to display a single document, or a collection of documents. For example, here’s the views/index.js file:

App.Views.Index = Backbone.View.extend({

initialize: function() {

this.render();

},

render: function() {

$(this.el).html(JST.documents_collection({ collection: this.collection }));

$('#app').html(this.el);

}

});

This code is called when CloudEdit needs to display a list of documents. You can see that it calls the “JST.documents_collection” function and passes in the collection of documents. This actually refers to the “documents_collect.jst” file, which in CloudEdit is saved in the app/views/documents folder, where you would normally find the server-side view code. And here’s what the documents-collection.jst file looks like:

<% if(collection.models.length > 0) { %>

<h3><a href='#new'>Create New</a></h3><ul>

<% collection.each(function(item) { <%

<li><a href='#documents/<%= item.id %>'><%= item.escape('title') %></a></li>

<% }); %>

</ul>

<% } else { %>

<h3>No documents! <a href='#new'>Create one</a></h3>

<% } %>

As James explains in part 2 of his tutorial, this resembles ERB code but is actually evaluated on the client side to display the list of documents. The variables “collection” and “item” refer to the Backbone collection and model objects used by CloudEdit.

Since CloudEdit is based on Rails 2.3.8, it uses the Jammit gem, also from DocumentCloud to package and download all of the client code, similar to how the Rails 3.1 asset pipeline works. James has configured Jammit to look for all of the Backbone code in the public/javascript folders above, and the JST files in the app/views folder.

Rails 3.1 and the asset pipeline

The asset pipeline, based on the Sprockets framework, is one of the most exciting innovations in Rails 3.1, along with CoffeeScript. If you’re not familiar with Sprockets already, a good place to get started would be to read the RailsGuides article on the asset pipeline (still only on edgeguides.rubyonrails.org). I also found Peter Cooper’s Ruby Inside article: How to Play with Rails 3.1, CoffeeScript and All That Jazz Right Now and Jack Dempsey’s post Rails 3.1: Understanding Sprockets and CoffeeScript very helpful.

With the asset pipeline, you can organize your client asset files like this (I'm leaving out the "lib/assets" folder, images and also gem folders):

Now all of the javascript, stylesheets and other static files are compressed and combined together into a single request.

Again, for me the most exciting thing about this is not the performance improvements related to reducing the number of HTTP requests and to compression... but that this is the first step towards a common convention for organizing where Javascript/client code files should go. What we’re missing is the MVC pattern that James Yu used with Backbone in CloudEdit. Where do the Backbone models go? What about the views? ... etc., etc.

Another cool project I just came across recently while working on the CloudEdit scaffold, is the backbone-rails gem from Code Brew Studios. This gem implements a Rails scaffold generator, among a couple of other things, that produces a scaffold app that runs entirely in a single page using Ajax and Backbone. To try it out yourself in a Rails 3.1 app just follow the simple instructions on their github readme page. I also plan to post a scaffold for this on ScaffoldHub sometime soon.

For their backbone-rails scaffold generator, Code Brew Studios have decided to use this directory structure:

Here we can see they’ve created the usual “model,” “controllers” and “views” folders right under app/assets/javascripts. This works well with Rails 3.1 and Sprockets since all of these files will be compiled and combined together. You can also see a folder called “templates/posts”. This folder holds files similar to the JST files we saw above in the CloudEdit example, but instead CodeBrew is using the EJS gem to preprocess their JST files on the server before later using them on the client side.

Here’s what the index_view.coffee file in the app/assets/javascripts/backbone/views/posts folder looks like:

Backbone_scaffold_test.Views.Posts ||= {}

class Backbone_scaffold_test.Views.Posts.PostView extends Backbone.View

template: JST["backbone/templates/posts/post"]

events:

"click .destroy" : "destroy"

tagName: "tr"

destroy: () ->

@options.model.destroy()

this.remove()

return false

render: ->

$(this.el).html(this.template(this.options.model.toJSON() ))

return this

This is CoffeeScript, which you can guess from the file extension, one of the other exciting innovations in Rails 3.1. I don’t have time to explain everything here today, but one important detail to notice here is that the view code calls JST["backbone/templates/posts/post"]. This refers to the post.jst.ejs JST template file, located in the app/assets/javascripts/backbone/templates/posts folder:

<td><%= title %></td> <td><%= content %></td> <td><a href="#/<%= id %>">Show</td> <td><a href="#/<%= id %>/edit">Edit</td> <td><a href="#/<%= id %>/destroy" class="destroy">Destroy</a></td>

Again, think of JST like a client side ERB transformation.

Conclusion

While it’s still not obvious how to organize your Javascript code files in a Rails project, I hope looking at these two examples sparked some ideas and will make you think twice about it. Remember, organizing your code files in directories is not simply a matter of housekeeping or typing: having a well organized project directory structure will lead to well organized code, and ultimately to a better application.

The recent asset pipeline changes in Rails 3.1 are very exciting for a lot of good reasons, but in my opinion the best thing about the asset pipeline is that it starts us down a longer road towards agreeing on a new convention for organizing client Javascript code files in a Rails project’s directory structure. I think ultimately this convention will turn out to be much more important and helpful than the HTTP performance improvements the asset pipeline offers.

During the next year or two, it will be very exciting to see whether the structure offered by Backbone for client code is integrated into Rails, or whether some other new Javascript framework will come along instead. With technologies like Backbone and also CoffeeScript it seems to me that the line between the client and server is becoming more and more blurred every year! We’ll have to just wait and see how it all turns out.