What Do Perl and Go Have in Common?

TL/DR: Both Perl and Go only partially implement object oriented programming, in a confusing way. Using either language you can create structures equivalent to objects but without using keywords such as class or new. Converting a Go function into a method by adding a receiver reminds me of "blessing" a Perl hash reference.

It’s hard to imagine two programming languages that are more different. Larry Wall created Perl almost 30 years ago in 1987. Google introduced Go much more recently in 2009. Perl is a dynamic, interpreted language while Go uses a compiler and static types. Perl syntax is quirky, fun and sometimes bizarre, while Go syntax is clean and simple, almost boring at times.

This year, coincidentally, I tried to learn both Perl and Go around the same time. Oddly, I found something in common between these two dramatically different languages. They both allow you to create objects and to write methods, but without supporting class, new or other keywords found in traditional object oriented languages like Smalltalk, Java, Ruby or Python. Both languages leave the door partially open to object oriented design, but don’t provide the syntax or features you expect and need for using objects and classes.

Writing a Perl Function

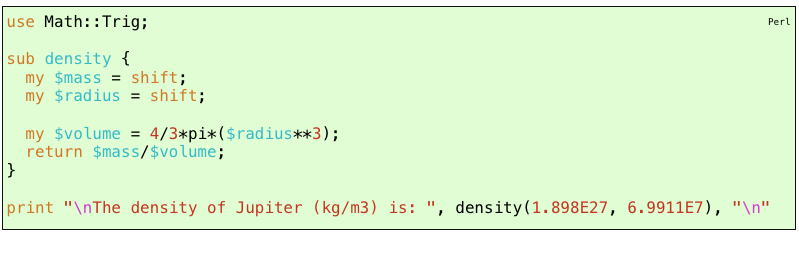

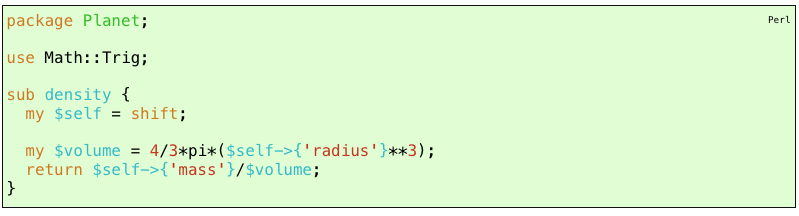

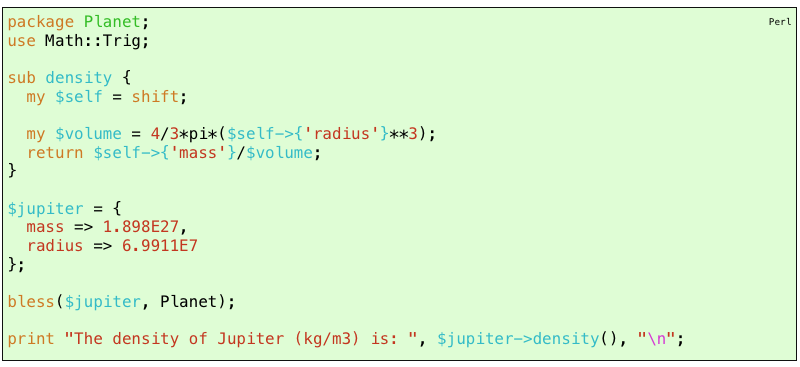

Let’s suppose I want to calculate the density of Jupiter, based on its mass and diameter. Using Perl, I could write:

Writing Perl feels like riding a vintage VW bus. Things don’t

work the way you expect, but you can always feel the love.

As you can see, Perl’s syntax is somewhat odd: The my keyword indicates each variable belongs to the local lexical scope. The shift keywords pull the mass and radius values from an array of values Perl implicitly passes to every function - Perl functions always take a single array argument! And you have to prefix all of the identifiers with either a $, @ or % character to indicate whether it is a scalar (simple value), an array or a hash. Sometimes in more complex Perl code you have to combine these prefixes together in cryptic patterns, such as @$var, or %$var. Thankfully in this simple function I just use numeric values, so $ is sufficient.

To me, Perl feels like an old-fashioned, awkward version of Ruby. And this makes some sense. Perl was to some extent the model for both Ruby and Python, which were created just a few years after Perl in the early 1990s. Ruby and Python smoothed out the rough edges of Perl’s syntax (along with adding proper support for objects among other things).

Creating a Perl Object

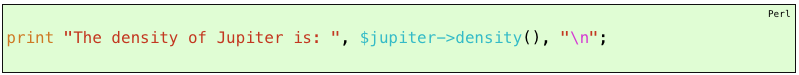

Now I decide to use an object oriented style instead. I want a Jupiter object which has mass and radius attributes, and I’d like the density function to be a method, like this:

In other words, I’d like to think of $jupiter as an instance of the Planet class.

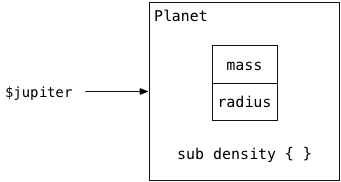

By writing a Planet class, I group together data values that describe each planet (mass and radius) with the functions that use those values (density). Object oriented languages refer to the data values as instance variables, and the functions as methods. By creating a class, I now have a natural place to gather functions and attributes related to planets.

The problem is that Perl isn’t an object oriented language. There’s no way to declare a class, define methods or create objects which are instances of that class. However, a few years after Perl was invented, in the mid 1990s, Larry Wall and the Perl team introduced some support for object oriented programming concepts in Perl 5. They converted Perl into an object oriented language after the fact - at least a partially object oriented language.

To create a Perl class, I first group my planet functions together using the Perl package keyword. In this example I have only one:

This gives me a place to put all of the methods of the Planet class - the package keyword plays the same role the class keyword would in Java or Ruby, to some extent. Also notice that I’ve rewritten my function to use object oriented syntax. Instead of obtaining the mass and radius from the parameters array, I get a single parameter which I call $self. Then I use $self as a hash reference to get the mass and radius values, for example: $self->{'mass'}. This is object oriented code. I’ve created a class and added a method to it.

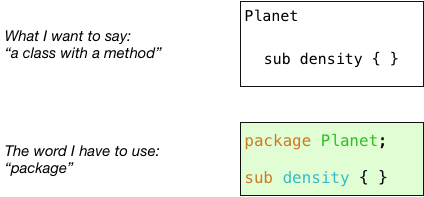

However, let’s think about this for another moment:

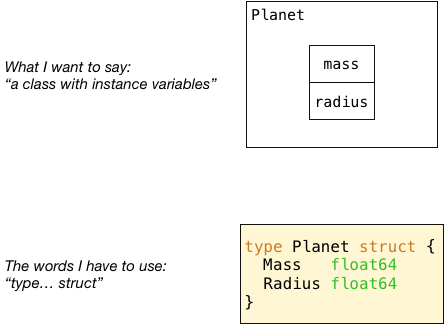

Notice there’s a difference between what I want to say, and the words I have to use to say it. The Perl language doesn’t include the class keyword; instead, I need to use package. We’ll see this again in a moment.

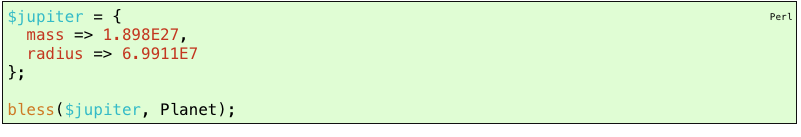

To create an instance of my new Planet class, an object, I need to create a hash (technically a reference to a hash) and then “bless” it:

This creates a connection between the hash (the object) and the package that contains the methods I want to use (the class). Now I can use syntax such as $jupiter->density(). I’ve done it! I’ve created an object using Perl.

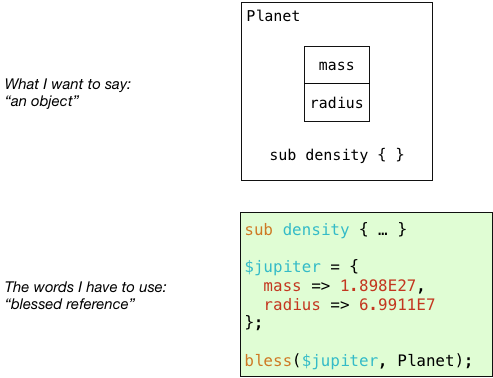

However, once again the language doesn’t supply the words I want to use to express the idea I’m thinking of:

Expressing Object Oriented Concepts Using Perl

Here’s the complete, object oriented version of my example:

To me, the Perl code I wrote above seems very confusing. But it’s not Perl’s strange, old-fashioned syntax that confuses me. After a while, all the $ symbols and the use of shift start to make sense. Writing Perl code is a bit like writing Ruby code while on drugs - I start with Ruby and just keep adding $ and semicolon characters until it works.

The real problem in this example is that Perl allows me to create objects and classes, but doesn’t refer to them as objects or classes. Instead, I have “blessed references” and “packages.” Perl allows me to get the object oriented behavior I want, but doesn’t let me use the words I want to use to describe what I’m doing. Perl’s partial support of object oriented programming is confusing at best.

Note: Perl 6, under development for the last fifteen years and still not released, is planning to introduce more explicit support for objects using the class and new keywords.

Writing Go code feels like riding in a Google driverless car:

the compiler and gofmt tool are in complete control.

Creating a Go Object

Perl was invented many years ago. Now let’s try using a modern, new programming language to write the same example: Go. Along the way I’ll compare the Go version with the Perl code I wrote above.

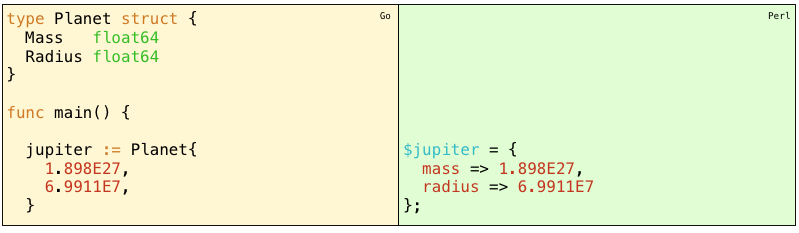

Earlier using Perl I had to use the package keyword to define a place to put my class’s methods. In Go, I define a group of methods in a different way: by associating them with a type. Therefore, I’ll start my Go code by creating a Planet type:

The two versions look very different. In Go I define a static type that always consists of mass and radius values, while in Perl I dynamically create a hash that might contain any values.

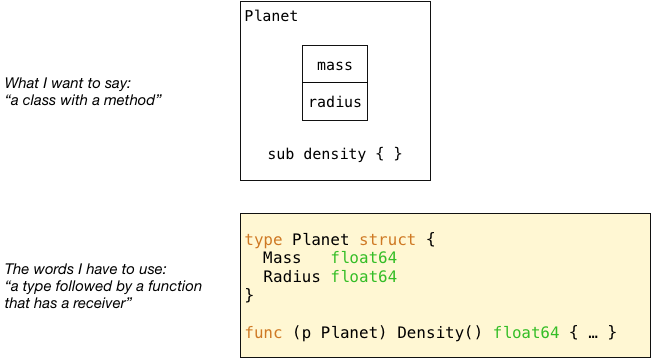

Once again, however, I’m forced to think about my code one way and write it another:

What Go and Perl really have in common is this: Neither language contains the words and syntax I really would like to use to express the object oriented concepts I’m trying to use.

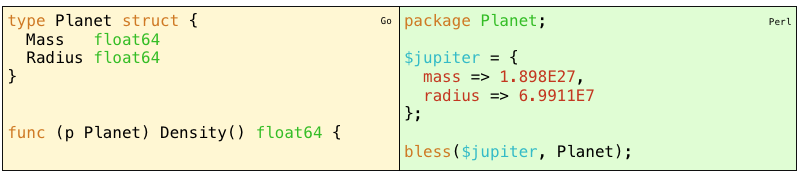

So far I’ve created a type, a static collection of values. Let’s take the next step and convert that into a class:

In Go I don’t need to connect my instance data with the class; the mass and radius values are already contained inside the Planet struct type. Instead, I need to create a connection between the method and the class. I do this by typing in a receiver for the Density function, func (p Planet) Density(), converting it into a method of the Planet type.

In Perl I “bless” a hash by connecting it to a group of functions in a package. A blessed hash is an object in Perl. In Go I “bless” a function by connecting it to a type containing instance data. A blessed function combined with a type is a class in Go. The two languages both use special syntax tricks to allow for object oriented programming, but they make the connection between instance variables and methods from opposite directions.

Once again, however, there’s an impedance mismatch between the concepts I’m imagining and the words I have to use to to express them:

Go doesn’t provide me with the vocabulary I want to use. I want to type class, but Go only allows me to use type struct. And because there’s no class keyword, my blessed function, my method, could be anywhere and not necessary right next to my type definition.

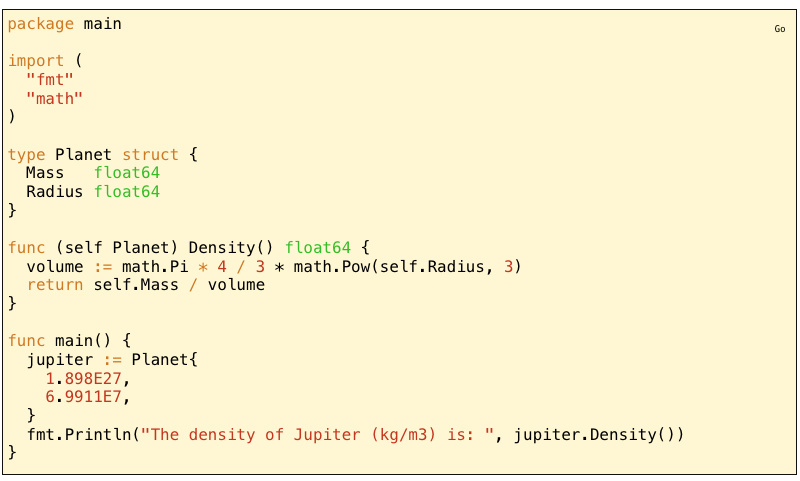

Expressing Object Oriented Concepts Using Go

Here’s the complete, object oriented version of my example in Go:

I find this Go code just as confusing and misleading as the Perl version above, and for the same reason. Both Perl and Go take the first step towards object oriented programming, but stop short of providing a complete solution. Instead of objects, Go gives us C-style static structures which can have methods associated with them. And Go doesn’t provide classes at all: There’s no natural place to gather all of the methods belonging to a given type.

We can guess that Perl 5 didn’t introduce proper support for object oriented programming either because it was too difficult to add it to an existing language, or for backward compatibility reasons. But the designers of Go decided from the very beginning not to support classes or objects. Then, why support methods at all? Why allow developers to create object-like structures, but with a confusing syntax? Or why not go all the way and introduce the class keyword to properly support object structures?

Go’s tepid, partial support for object oriented programming reminds me of Perl. Writing a Go function and making it special - “blessing” it - by assigning it a receiver reminds me of how I would bless a hash in a Perl program. Perhaps Google used Perl as design inspiration for Go; perhaps they wanted to include a small bit of Perl’s quirky, bizarre but lovable behavior in Go.

Regardless, don’t stretch your programming language by using it in ways it wasn’t intended to be used. And certainly don’t change your ideas and solutions to fit any given programming language. Choose the programming language that has keywords and syntax that allow you to express your ideas in a natural, straightforward manner. The only purpose of a language, whether a human language or programming language, is to express our abstract thoughts using words in simple, or even beautiful, ways.