The Start of a Long Journey: How Ruby Parses and Compiles Your Code

This is an excerpt from the beginning of an eBook I’m writing this Summer called “Ruby Under a Microscope.” My goal is to teach you how Ruby works internally without assuming you know anything about the C programming language.

If you’re interested in Ruby internals you can sign up here and I’ll send you an email when the eBook is finished. Next week I’m planning to publish part of the following chapter also, which will cover how Ruby’s YARV engine executes your code after it’s been compiled. You might also want to check out an entire chapter from the book I posted last month. I’m having the time of my life researching and writing this - I hope you’ll find learning about what’s going on inside Ruby as fascinating and fun as I do!

|

How many times do you think Ruby reads and transforms your code before running it? Once? Twice?

Whenever you run a Ruby script - whether it’s a large Rails application, a simple Sinatra web site, or a background worker job, Ruby rips your code apart into small pieces and then puts it back together in a different format... three times! Between the time you type “ruby” and start to see actual output on the console, your Ruby code has a long road to take, a journey involving a variety of different technologies, techniques and open source tools.

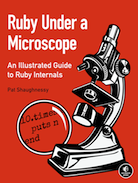

At a high level, here’s what this journey looks like:

First, Ruby tokenizes your code. During this first step, Ruby reads the text characters in your code file and converts them into tokens. Think of tokens as the words that are used in the Ruby language. In the next step, Ruby parses these tokens; “parsing” means to group the tokens into meaningful Ruby statements. This is analogous to grouping words into sentences. Finally, Ruby compiles these statements or sentences into low level instructions that later Ruby can execute using a virtual machine.

I’ll get to Ruby’s virtual machine called “Yet Another Ruby Virtual Machine” (YARV) next in Chapter 2, but first in this chapter I’ll describe the tokenizing, parsing and compiling processes Ruby uses to understand and process the code you give it. Join me as I follow a Ruby script on its journey!

Tokens: the words that make up the Ruby language

… read it in the finished eBook.

Experiment 1-1: Using Ripper to tokenize different Ruby scripts

… read it in the finished eBook.

Parsing: how Ruby understands the code you write

|

| Ruby uses an LALR parser generator called Bison |

Now that Ruby has converted your code into a series of tokens, what does it do next? How does it actually understand and run your program? Does Ruby simply step through the tokens and execute each one in order?

No, it doesn’t... your code still has a long way to go before Ruby can run it. As I said above, the next step on your code’s journey through Ruby is called “parsing,” which is the process for grouping the words or tokens into sentences or phrases that make sense to Ruby. It is during the parsing process Ruby that takes order of operations, methods and arguments, blocks and other larger code structures into account. But how does Ruby do this? How can Ruby or any language actually “understand” what you’re telling it with your code? For me, this is one of the most fascinating areas of computer science… endowing a computer program with intelligence.

Ruby, like many programming languages, uses something called an “LALR parser generator” to process the stream of tokens that we just saw above. Parser generators were invented back in the 1960s; like the name implies, parser generators take a series of grammar rules and generate code that can later parse and understand tokens that follow those rules. The most widely used and well known parser generator is called Yacc (“Yet Another Compiler Compiler”), but Ruby instead uses a newer version of Yacc called Bison, part of the GNU project. The term “LALR” describes how the generated parser actually works internally - more on that below.

Bison, Yacc and other parser generators require you to express your grammar rules using “Backus–Naur Form” (BNF) notation. For Bison and Yacc, this grammar rule file will have a “.y” extension, named after “Yacc.” The grammar rule file in the Ruby source code is called “parse.y” - the same file I mentioned above that contains the tokenize code. It is in this parse.y file that Ruby defines the actual syntax and grammar that you have to use while writing your Ruby code. The parse.y file is really the heart and soul of Ruby - it is where the language itself is actually defined!

Ruby doesn’t use Bison to actually process the tokens; instead, Ruby runs Bison ahead of time during Ruby’s build process to create the actual parser code. There are really two separate steps to the parsing process, then:

Ahead of time, before you ever run your Ruby program, the Ruby build process uses Bison to generate the parser code (parse.c) from the grammar rules file (parse.y). Then later at run time this generated parser code actually parses the tokens returned by Ruby’s tokenizer code. You might have built Ruby yourself from source manually or automatically on your computer by using a tool like Homebrew. Or someone else may have built Ruby ahead of time for you if you installed Ruby with a prepared install kit.

Now let’s learn about how grammar rules work - the best way to become familiar with grammar rules is to take a close look at one simple example. Suppose I want to translate from the Spanish:

Me gusta el Ruby

...to the English:

I like Ruby

… and that to do this suppose I use Bison to generate a C language parser from a grammar file. Using the Bison/Yacc grammar rule syntax - the “Backus–Naur” notation - I can write a simple grammar rule like this with the rule name on the left, and the matching tokens on the right:* (*footnote: This is actually a slightly modified version of BNF that Bison uses - the original BNF syntax would have used ‘::=’ instead of a simple ‘:’ character.)

SpanishPhrase : me gusta el ruby { printf("I like Ruby\n"); }

This grammar rule means: if the token stream is equal to “me”, “gusta,” “el” and “ruby” - in that order - then we have a match. If there’s a match the Bison generated parser will run the given C code, the “printf” statement (similar to “puts” in Ruby), which will print out the translated English phrase.

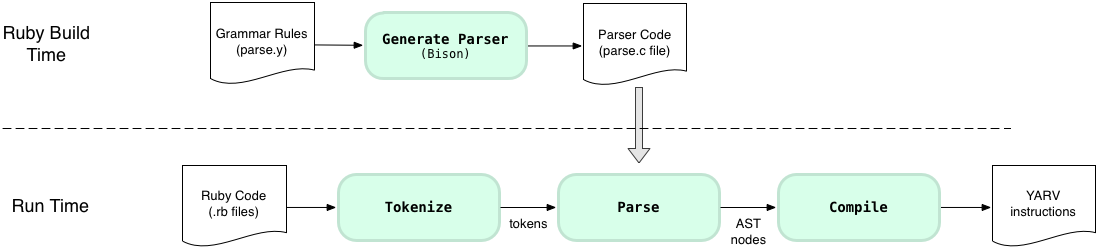

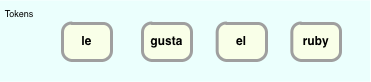

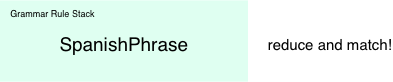

How does this work? Here’s a conceptual picture of the parsing process in action:

At the top I show the four input tokens, and the grammar rule right underneath it. It’s obvious in this case there’s a match since each input token corresponds directly to one of the terms on the right side of the grammar rule. In this example we have a match on the “SpanishPhrase” rule.

Now let’s change the example to be a bit more complex: suppose I need to enhance my parser to match both:

Me gusta el Ruby

and:

Le gusta el Ruby

...which means “She/He/It likes Ruby.” Here’s a more complex grammar file that can parse both Spanish phrases:* (*footnote: again this is a modified version of BNF used by Bison - the original syntax from the 1960s would use “< >” around the child rule names, like this for example: “VerbAndObject ::= <SheLikes> | <ILike>”)

SpanishPhrase: VerbAndObject el ruby { printf("%s Ruby\n", $1); }; VerbAndObject: SheLikes | ILike { $$ = $1; }; SheLikes: le gusta { $$ = "She likes"; } ILike: me gusta { $$ = "I like"; }

There’s a lot more going on here; you can see four grammar rules instead of just one, and also I’m using the Bison directive “$$” to return a value from a child grammar rule to a parent, and “$1” to refer to a child’s value from a parent. Also, the second rule for VerbAndObject includes an OR operator, the vertical bar character.

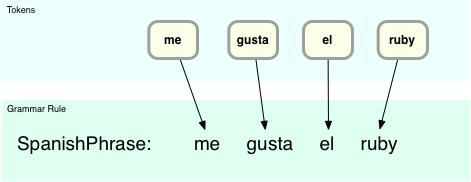

Now things aren’t so obvious - the parser can’t immediately match any of the grammar rules like in the previous, trivial example:

Here using the “SpanishPhrase” rule the “el” and “ruby” tokens match, but “le” and “gusta” do not. Ultimately we’ll see how the child rule “VerbAndObject” does match “le gusta” but for now there is no immediate match. And now that there are four grammar rules, how does the parser know which one to try to match against? ..and against which tokens?

This is where the real intelligence of the LALR parser comes into play. This acronym describes the algorithm the parser uses to find matching grammar rules, and means “Look Ahead LR parser.” We’ll get to the “Look Ahead” part in a minute, but let’s start with “LR:”

- “L” (left) means the parser moves from left to right while processing the token stream; in my example this would be: le, gusta, el, ruby.

- “R” (reversed rightmost derivation) means the parser uses a bottom up strategy for finding matching grammar rules, by using a shift/reduce technique.

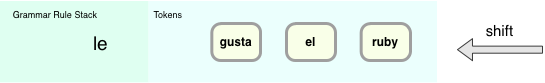

Here’s how the algorithm works for this example. First, the parser takes the input token stream:

… and shifts the tokens to the left, creating something I’ll call the “Grammar Rule Stack:”

Here since the parser has processed just one token, “le,” this is kept in the stack alone for the moment. “Grammar Rule Stack” is a simplification; in reality the parser does use a stack, but instead of grammar rules it pushes numbers onto its stack that indicate which grammar rule it just parsed. These numbers - or states from a state machine - help the parser keep track of where it is as it processes the tokens.

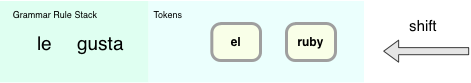

Next, the parser shifts another token to the left:

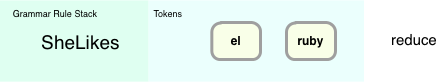

Now there are two tokens in the stack on the left. At this point the parser stops to examine all of the different grammar rules and looks for one that matches. In this case, it finds that the “SheLikes” rule matches:

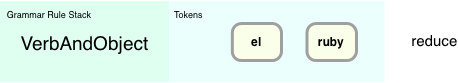

This operation is called “reduce,” since the parser is replacing the pair of tokens with a single, matching rule. This seems very straightforward… the parser just has to look through the available rules and reduce or apply the single, matching rule.

Now the parser in our example can reduce again - now there is another matching rule: VerbAndObject! This rule matches because of the OR (vertical bar) operator: it matches either the “SheLikes” or the “ILike” child rule. The parser can next replace “SheLikes” with “VerbAndObject:”

But let’s stop for a moment and think about this a bit more carefully: how did the parser know to reduce and not continue to shift tokens? Also, in the real world there might actually be many matching rules the parser could reduce with - how does it know which rule to use? This is the crux of the algorithm that LALR parsers use... that Ruby uses… how does it decide whether to shift or reduce? And if it reduces, how does it decide which grammar rule to reduce with?

In other words, suppose at this point in the process…

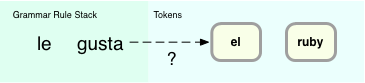

… there were multiple matching rules that included “le gusta.” How would the parser know which rule to apply or whether to shift in the ‘el’ token first before looking for a match?

Here’s where the “LA” (Look Ahead) portion of LALR comes in: in order to find proper matching rule it looks ahead at the next token:

Additionally, the parser maintains a state table of possible outcomes depending on what the next token was and which grammar rule was just parsed. LALR parsers are complex state machines that match patterns in the token stream. When you use Bison to generate the LALR parser, Bison calculates what this state table should contain based on the grammar rules you provided. In this example, the state table would contain an entry indicating that if the next token was “el” the parser should first reduce using the SheLikes rule, before shifting a new token.

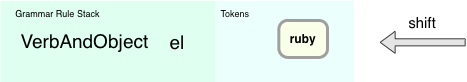

I won’t show the details of what a state table looks like; if you’re interested, the actual LALR state table for Ruby can be found in the generated parse.c file. Instead let’s just continue the shift/reduce operations for my simple example. After matching the “VerbAndObject” rule, the parser would shift another token to the left:

At this point no rules would match, and the state machine would shift another token to the left:

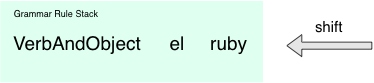

And finally, the parent grammar rule “SpanishPhrase” would match after a final reduce operation:

Why have I shown you this Spanish to English example? Because Ruby parses your program in exactly the same way! Inside the Ruby “parse.y” source code file, you’ll see hundreds of rules that define the structure and syntax of the Ruby language. There are parent and child rules, and the child rules return values the parent rules can refer to in exactly the same way, using the $$, $1, $2, etc. symbols. The only real difference is scale - my Spanish phrase grammar is extremely simple, trivial really. On the other hand, Ruby’s grammar is extremely complex, an intricate series of interrelated parent and child grammar rules, which sometimes even refer to each other in circular, recursive patterns. But this complexity just means that the generated state table in the parse.c file is larger. The basic LALR algorithm - how the parser processes tokens and uses the state table - is the same.

Let’s take a quick look at some of the actual Ruby grammar rules from parse.y. Here’s my example Ruby script from the last section on tokenization:

10.times do |n| puts n end

This is a very simple Ruby script, right? Since this is so short, it should’t be too difficult to trace the Ruby parser’s path through its grammar rules. Let’s take a look at how it works:

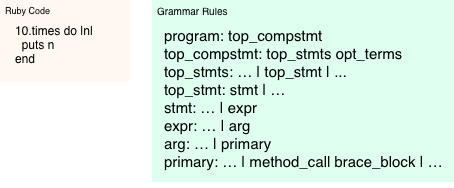

On the left I show the code that Ruby is trying to parse. On the right are the actual matching grammar rules from the Ruby parse.y file, shown in a simplified manner. The first rule, “program: top_compstmt” is the root grammar rule which matches every Ruby program in its entirety. As you follow the list down, you can see a complex series of child rules that also match my entire Ruby script: “top statements,” a single statement, an expression, an argument and finally a “primary” value.

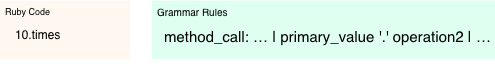

Once Ruby’s parse reaches the “primary” grammar rule, it encounters a rule that has two matching child rules: “method_call” and “brace_block.” Let’s take the method_call rule first:

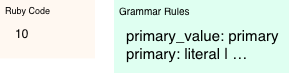

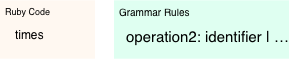

The method_call rule matches the “10.times” portion of my Ruby code - i.e. where I call the “times” method on the 10 Fixnum object. You can see the rule matches another primary value, followed by a period character, followed in turn by an “operation2”. The period is simple enough, and here’s how the primary_value and operation2 child rules work: first the “primary_value” rule matches the literal “10:”

And then the “operation2” rule matches the method name “times:”

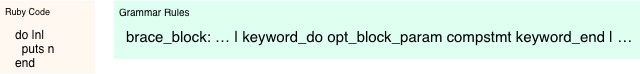

What about the rest of my Ruby code? How does Ruby parse the contents of the “do … puts… end” block I passed to the times method? Ruby handles that using the “brace_block” rule from above:

I won’t go through all the remaining child grammar rules here, but you can see how this rule in turn contains a series of other matching child rules:

- “keyword_do” matches the “do” reserved keyword

- “opt_block_param” matches the block parameter “|n|”

- “compstmt” matches the contents of the block itself - “puts n,” and

- “keyword_end” matches the “end” reserved keyword

… read the rest of this section in the finished eBook.

Experiment 1-2: Using Ripper to parse different Ruby scripts

… read it in the finished eBook.

How Ruby compiles your code into a new language!

… read it in the finished eBook.

Experiment 1-3: Using the RubyVM class to display YARV instructions

… read it in the finished eBook.

How the JRuby team is implementing a new instruction set

… read it in the finished eBook.

An elegant dance: how Rubinius uses Ruby and C together to parse your code

… read it in the finished eBook.