The technology you never knew you were using to test your Rails site

|

| Libxml2 powers your BDD/integration tests that use the default Capybara driver |

If you’re a Rails developer using Behavior Driven Development, then you’re probably using either Cucumber features or RSpec integration tests with the Capybara gem to simulate what a user would do with a real browser. You probably know that by default Capybara uses a driver based on Rack to connect to your Rails app and make simulated HTTP requests, all within the same process using only Ruby.

But what you probably didn’t know is that indirectly Capybara uses a large, complex open source C library called Libxml2 to parse the HTML returned by your site, and to run assertions against it. It’s interesting to me that each time I run a Cucumber BDD test on a Ruby on Rails web site, the HTML I’m trying to inspect and test is passed into a C library... in other words, that my Cucumber tests are actually implemented by C code I never even knew I had on my machine.

An example Rails BDD/integration test

Let’s start by taking a look at a typical Cucumber feature:

{^rx:Scenario:^} Viewing the home page

{^kw:Given^} I am on the home page

{^cl:Then^} I should see "This is a simple web page."

This tests one of the web pages in a Rails app, the “home page,” and checks whether the text “This is a simple web page.” appears on it. You could just as easily have written this by calling Capybara directly from RSpec:

describe 'the text on the home page' do it 'should explain what to do next' do visit '/' page.should have_content('This is a simple web page.') end end

In either case there are two steps to the test:

- Load the home page using a simulated HTTP request via Rack, and

- Assert that “This is a simple web page” appears on that page, i.e. in the HTML response returned by your Rails web site.

In a future blog post I may look at step 1 in more detail: how does Capybara simulate the HTTP request via Rack? But for today I’ll just assume that Capybara somehow calls the target Rails application and saves the response away in an internal variable. Instead, let’s take a closer look at step 2: how does Capybara assert something about your web site’s page, the home page in this example? In other words, how does the call to page.should have_content(...) work?

Capybara, Nokogiri and Libxml2

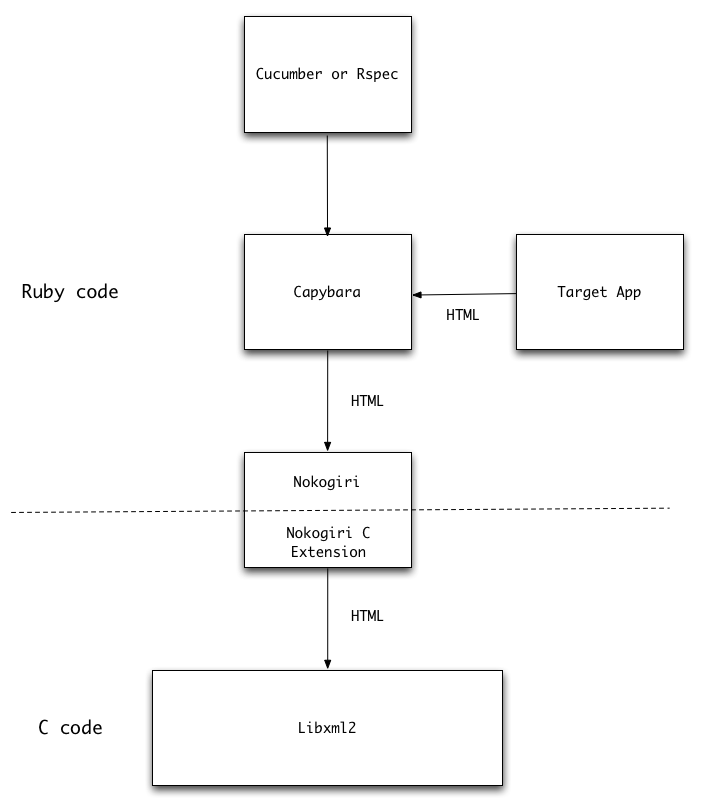

It turns out that Capybara does this by parsing the HTML returned by the home page request using a gem called Nokogiri, which, in turn, uses the Libxml2 C library to perform the actual HTML parsing work. Here’s a diagram summarizing all of this:

All of the code above the dashed line is Ruby, while the code below the line is C. I show Nokogiri straddling the dashed line, since it actually uses both C and Ruby code. Nokogiri contains “C extension code;” you can find this inside the gem’s “ext” folder. For Nokogiri you can look here on github to see its C extension code. C extension code allows a gem author to write functions in C that can be called by their Ruby code. C extension code, therefore, often plays the role of a bridge between Ruby and other C code in the application. When you install a Ruby gem containing C extension code, you’ll see the message “Compiling native extensions” appear - this means that Rubygems has called your C compiler to produce the native binaries needed to run the code on your platform.

Nokogiri is a high level, elegant, Ruby abstraction layer on the Libxml2 library, and provides Ruby clients with a simple way to parse XML, HTML and also to use XPath operations to search through the DOM (Document Object Model) returned by Libxml2. Nokogiri uses its C extension code to call the Libxml2 C API functions, and convert data between the format Ruby uses and the format the C Libxml2 API requires.

Proving that Cucumber BDD tests use the Libxml2 C library

Next, let’s take a look at exactly how Nokogiri is calling Libxml2, and prove that this C library is being used in my example Cucumber test. Here’s the documentation for C Libxml2 API call used by Nokogiri to parse HTML (from: http://xmlsoft.org/html/libxml-HTMLparser.html#htmlReadMemory):

Function: htmlReadMemory

htmlDocPtr htmlReadMemory (const char * buffer,

int size,

const char * URL,

const char * encoding,

int options)

parse an XML in-memory document and build a tree.

buffer: a pointer to a char array

size: the size of the array

URL: the base URL to use for the document

encoding: the document encoding, or NULL

options: a combination of htmlParserOption(s)

Returns: the resulting document tree

This C function is what actually parses the HTML text, and is located inside the Libxml2 library. You can see its declaration inside the HTMLparser.h header file, which on my machine is located in /usr/include/libxml2/libxml/HTMLparser.h. Depending on how you installed Libxml2 (homebrew, macports, from source) this will be located in a different location.

This is called from the Nokogiri Ruby gem’s C extension code, in the ext/nokogiri/html_document.c file:

/* * call-seq: * read_memory(string, url, encoding, options) * * Read the HTML document contained in +string+ with given +url+, +encoding+, * and +options+. See Nokogiri::HTML.parse */ static VALUE read_memory( VALUE klass, VALUE string, VALUE url, VALUE encoding, VALUE options ) { const char * c_buffer = StringValuePtr(string); const char * c_url = NIL_P(url) ? NULL : StringValuePtr(url); const char * c_enc = NIL_P(encoding) ? NULL : StringValuePtr(encoding); int len = (int)RSTRING_LEN(string); VALUE error_list = rb_ary_new(); VALUE document; htmlDocPtr doc; /* Added by Pat: */ fprintf(stderr, "DEBUG: the HTML passed from Capybara and Nokogiri to Libxml2 is:\n"); fprintf(stderr, c_buffer); fprintf(stderr, "DEBUG: end.\n"); xmlResetLastError(); xmlSetStructuredErrorFunc((void *)error_list, Nokogiri_error_array_pusher); doc = htmlReadMemory(c_buffer, len, c_url, c_enc, (int)NUM2INT(options)); xmlSetStructuredErrorFunc(NULL, NULL); if(doc == NULL) { xmlErrorPtr error; xmlFreeDoc(doc); error = xmlGetLastError(); if(error) rb_exc_raise(Nokogiri_wrap_xml_syntax_error((VALUE)NULL, error)); else rb_raise(rb_eRuntimeError, "Could not parse document"); return Qnil; } document = Nokogiri_wrap_xml_document(klass, doc); rb_iv_set(document, "@errors", error_list); return document; }

I added the three fprintf lines at the top of the C function which will print out the HTML that is passed in from Capybara to Nokogiri on its way to Libxml2. Now if we manually recompile the C extension code in Nokogiri:

$ cd ~/.rvm/gems/ruby-1.8.7-p352/gems/nokogiri-1.5.0/ext/nokogiri $ make $ make install /usr/bin/install -c -m 0755 nokogiri.bundle /Users/pat/.rvm/gems/ruby-1.8.7-p352/gems/nokogiri-1.5.0/lib/nokogiri

...and run the Cucumber test back in my Ruby app, we’ll see the HTML on it’s way to the Libxml2 library!

$ bundle exec cucumber features/view_web_page.feature

Using the default profile...

Feature: View the home page

As a web visitor

I want to be able to view the home page

In order to find out what else is on this web site

Scenario: Viewing the home page # features/view_web_page.feature:6

{^s:Given I am on the home page^} # features/step_definitions/web_steps.rb:44

DEBUG: the HTML passed from Capybara and Nokogiri to Libxml2 is:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>SimpleWebApp</title>

<link href="/assets/application.css" media="screen" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" />

<script src="/assets/application.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

</head>

<body>

This is a simple web page.