Is Ruby interpreted or compiled?

|

Both JRuby and Rubinius can compile your

Ruby code into machine language! |

Ever since I started to work with Ruby in 2008, I’ve always assumed that it was an interpreted language like PHP or Javascript - in other words, that Ruby read in, parsed and executed my code all at runtime, at the moment my program was run. This seemed especially obvious since the default and most popular implementation of Ruby is called “MRI,” short for “Matz’s Ruby Interpreter.” I always thought it was necessary to use an interpreter to make all of the dynamic features of the language possible.

However, it turns out that both JRuby and Rubinius, two other popular implementations of Ruby, support using a compiler the same way you would with a statically typed language like C or Java. Both JRuby and Rubinius first compile your Ruby code to byte code, and later execute it.

Today I’m going to show you how to use these Ruby compilers, and I’ll also take a peek under the hood to see what they produce internally. Possibly you’ll rethink some of your assumptions about how Ruby works along the way.

Using the Rubinius compiler

Using the Rubinius compiler is as simple as running any Ruby script. Here’s a very silly but simple Ruby program I’ll use as an example today:

class Adder

def add_two(x)

x+2

end

end

puts Adder.new.add_two(3)

Now if I save that into a file called “simple.rb,” switch to Rubinius using RVM, and run the script I’ll get the number “5” as expected:

$ rvm rbx-1.2.4-20110705

$ ruby simple.rb

5

Not very interesting, I know. But what is interesting is that when I ran simple.rb Rubinius created a new, hidden directory called “.rbx” with a strange, cryptically named file in it:

$ ls -a

. .. .rbx simple.rb

$ find .rbx

.rbx

.rbx/a7

.rbx/a7/a7fc1eb2edc84efed8db760d37bee43753483f41

This vaguely reminds me of how git saves the git repository data in a hidden folder called “.git,” also using cryptic hexadecimal names. What we are looking at here is a compiled version of simple.rb: the “a7fc1eb2e...” file contains my Ruby code converted into Rubinius byte code.

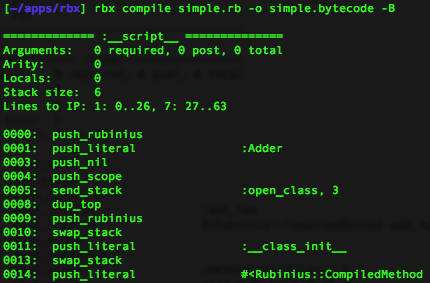

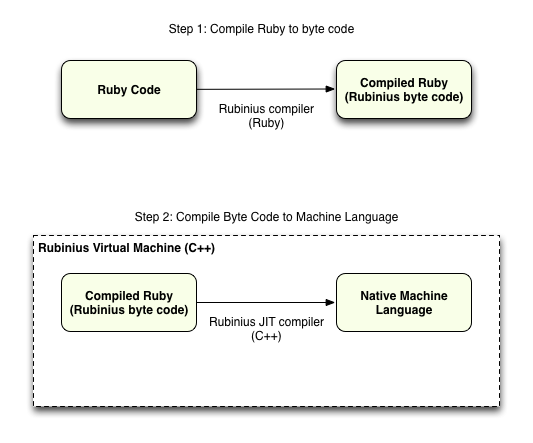

Whenever you run a Ruby script, Rubinius uses a two step process to compile and run your code:

On the top you can see that first Rubinius compiles your code into byte code, and then below later executes it using the Rubinius Virtual Machine, which can compile the byte code into native machine language. Rubinius also caches the byte code using the hexadecimal naming scheme I showed above, avoiding the need for the compile step entirely if the Ruby source code file didn’t change.

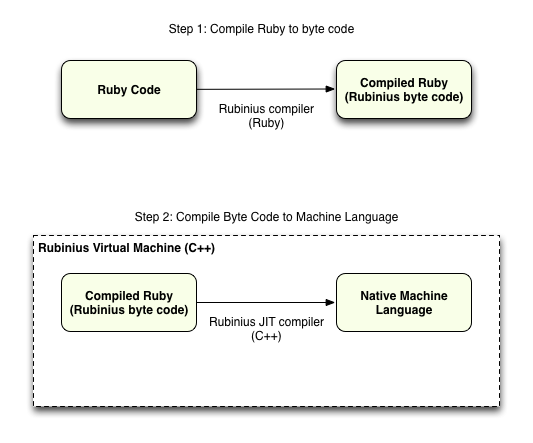

As Brian Ford explained on the Rubinius blog, you can actually run the Rubinius compiler directly like this:

$ rbx compile simple.rb -o simple.bytecode

This compiles my Ruby code and saves the byte code in the specified file. If we look at the simple.bytecode file, we’ll see a series of alphanumeric tokens that don’t make any sense. But if you run the compiler using the “-B” option you can see an annotated version of the Rubinius byte code:

$ rbx compile simple.rb -o simple.bytecode -B

============= :__script__ ==============

Arguments: 0 required, 0 post, 0 total

Arity: 0

Locals: 0

Stack size: 6

Lines to IP: 1: 0..26, 7: 27..63

0000: push_rubinius

0001: push_literal :Adder

0003: push_nil

0004: push_scope

0005: send_stack :open_class, 3

... etc ...

=============== :add_two ===============

Arguments: 1 required, 0 post, 1 total

Arity: 1

Locals: 1: x

Stack size: 3

Lines to IP: 2: -1..-1, 3: 0..5

0000: push_local 0 # x

0002: meta_push_2

0003: meta_send_op_plus :+

0005: ret

... etc ...

At the bottom here we can see the compiled version of my silly add_two method. It’s actually somewhat easy to understand the byte code, since it’s annotated so well:

- First “push_local” saves the value of the “x” parameter on the virtual machine stack.

- Then it pushes the literal value 2.

- Then it executes the + operation.

- And finally it returns.

The Rubinius virtual machine reminds me of those old “reverse polish” calculators from the 1980s, in which you would enter values on a stack in a similar way. As I discussed 3 weeks ago, the Rubinius source code is actually quite easy to understand since a large portion of it is actually written in Ruby, while the rest is written in well documented C++. The Rubinius compiler is no exception: it’s actually written in Ruby too! If you’re interested, you can see how the Rubinius compiler works without having to understand C++ at all. To get started take a look in the “lib/compiler” directory.

The Rubinius virtual machine, which runs the Rubinius byte code, is implemented in C++ and leverages an open source project called LLVM. Like JRuby, it uses a “Just In Time” compiler to convert the byte code to machine language at runtime. This means that your Ruby code, for example the add_two method above, ends up being converted into native machine language and run directly by your computer’s hardware!

Using the JRuby compiler

Now let’s take a look at how JRuby compiles Ruby code; I’ll start by using RVM to switch over to JRuby, and then I’ll run the same simple.rb script:

$ rvm jruby-head

$ ruby simple.rb

5

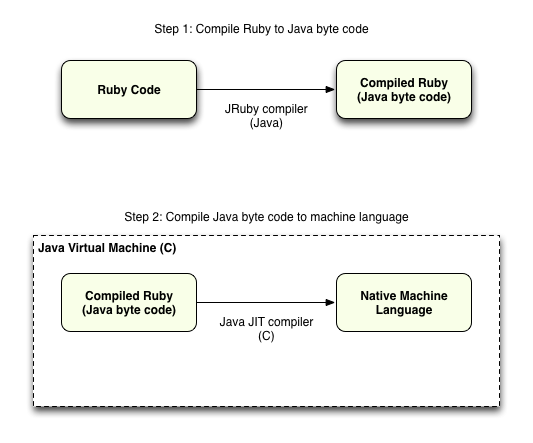

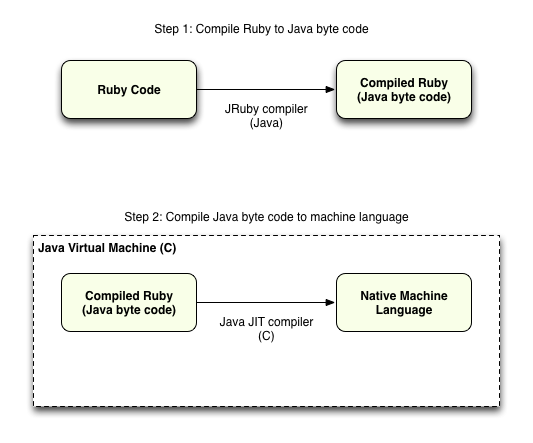

No surprise: we get the same result. At a high level, JRuby uses the same two step process to run your script - first it compiles the Ruby code into byte code, and then executes the byte code using the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). See my post last week called Journey to the center of JRuby to learn more about this.

Here's another diagram showing the two step process, this time for JRuby:

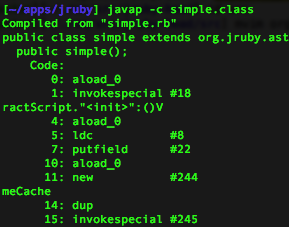

Like with Rubinius, it’s possible to run the JRuby compiler directly using the “jrubyc” command... following the Java executable naming pattern (“java” -> “javac”). Thanks to my friend Alex Rothenberg for pointing this out. Running “jrubyc” will create a Java .class file, which we can inspect using the Java decompiler like I did last week:

$ jrubyc simple.rb

$ ls

simple.class simple.rb

$ javap -c simple.class > simple.bytecode

Now the simple.bytecode file will contain an annotated version of the Java byte code the JVM will execute. Unlike Rubinius, which creates byte code that is fairly clean, simple and easy to understand, Java byte code is much more cryptic and confusing. Searching through the simple.bytecode file for my method add_two, I found the following snippet of byte code:

public static org.jruby.runtime.builtin.IRubyObject method__1$RUBY$add_two(simple, org.jruby.runtime.Thread...

Code:

0: aload_3

1: astore 9

3: aload_1

4: aload_2

5: aload 9

7: invokedynamic #80, 0 // InvokeDynamic #1:"fixnumOperator:+":(Lorg/jruby/runtime/Thread...

12: areturn

Although quite difficult to understand, there are a couple of important details to notice:

First, JRuby has compiled my Ruby add_two method into a byte code method called method__1$RUBY$add_two. This proves that my Ruby script has been compiled! That is, when JRuby ran simple.rb above, it did not read the Ruby code, interpret it and just follow the instructions like the MRI interpreter would do. Instead, it converted my Ruby script into byte code, and specifically my add_two method into the byte code snippet above.

Second, notice the use of the “invokedynamic” byte code instruction. This is a new innovation of the Java Virtual Machine, making it easier for the JVM to support dynamic languages like Ruby. Here you can see it’s used by the add_two method to call the + operator of the Ruby Fixnum class, for my x+2 Ruby code. If you’re interested in what invokedynamic actually means, be sure to check out a very detailed post Charles Nutter wrote about it back in 2008. This use of invokedynamic is actually new for Java 1.7 and JRuby 1.7, so if you’re using the current release version of JRuby (1.6.4) or earlier you won’t see it appear in the byte code.

Finally, as I explained last week since the JVM uses a Just In Time (JIT) compiler, all of the byte code you see above - in other words my Ruby script including the add_two method - will be compiled directly into native machine language if the JVM notices that it is called enough times, that it’s in a “hotspot.”

Why look under the hood? Who cares how Ruby works?

Today I’ve shown you some of the internal, technical details of Rubinius and JRuby. Many of you might find this boring and unimportant: who cares how Ruby works internally? All I care about is that my Ruby program works. And from one point of view that is all that really matters.

However, I find Ruby internals to be fascinating... I really do like having at least a small understanding of what’s going on inside of Ruby while it’s running my code. I also believe it will help me to become a more effective and knowledgeable Ruby developer, even if I never contribute a line of internal code to Rubinius, JRuby or MRI. And studying Ruby internals has definitely lead me to a number of surprising discoveries, and forced me to rethink the mental model I have always had of the Ruby interpreter... or should I say, the Ruby compiler!